Admin

-

Posts

7,474 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Gallery

Community Map

Posts posted by Admin

-

-

Metzeler Karoo 4 Tyres and the BMW R 1300 GS (Metzeler/)Metzeler Press Release:

The scene of the expedition, which represented an extreme challenge for motorbikes, tyres and riders, was El Circuito de los Seis Miles, in the Atacama Desert, Chile, the highest chain of active volcanoes in the world, which includes the Nevado Ojos del Salado and the Nevado de Incahuasi.

Stock motorbikes and standard tyres took on an extreme challenge. A team representing the METZELER brand and BMW Motorrad, riding a fleet of BMW R 1300 GS equipped with Metzeler Karoo 4 tyres, reached, and surpassed 6000 metres above sea level, starting from the sea, in less than 24 hours. A very difficult ascent for riders, motorbikes, and tyres, culminated on the notorious North face of Nevado Ojos del Salado, where the expedition reached 6006 metres in just 19 hours and 22 minutes, ultimately reaching a maximum altitude of 6027 metres.

The expedition involved an acclimatisation route ascending the Circuito de los Seis Miles, on the slopes of Nevado Ojos del Salado, located exactly on the border between Argentina and Chile. At 6891 metres, it is the highest active volcano in the world, and its twin, the Nevado de Incahuasi, 6610 metres high. The BMW R 1300 GS equipped with Metzeler Karoo 4 tyres then descended to sea level on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, in Bahia Inglesa. They departed at 3:00 PM local time on December 6th, crossing the Atacama Desert to reach Nevado Ojos Del Salado, successfully surpassing 6000 metres above sea level in less than 24 hours. The goal was achieved at 10:22 AM on December 7th.

The riders who were onboard entirely stock BMW R 1300 GS’s with Metzeler tyres were Salvatore Pennisi, Metzeler Testing and Technical Relation Director, Christof Lischka, Head of BMW Motorrad Development, Michele Pradelli, Italian extreme enduro champion and tester for the Italian magazine InMoto plus Karsten Schwers, tester and journalist for the German magazine Motorrad.

Salvatore Pennisi, Director of Testing and Technical Relations at Metzeler, stated: “This expedition has allowed us to confirm the strong relationship between Metzeler and BMW Motorrad but above all to demonstrate the value of two strictly standard products that anyone can purchase and use even in the most challenging conditions. The ascent to 6000 metres was extremely tough, especially for our crew who had to undergo a demanding physical preparation before getting on the bikes. So, even before expressing our joy for the effectiveness of our tyres, congratulations to the riders are a must.”

The new BMW R 1300 GS, in the sizes 120/70 R19 front and 170/60 R17 rear, uses Metzeler Tourance Next 2 tyres as original equipment on all versions, while Metzeler Karoo 4 are offered as an optional fitment for the off-road use. With the Metzeler Karoo 4 tyres the BMW R 1300 GS expresses perfect riding characteristics in off-road use and in the search for adventure.

These tyres, created to be multi-purpose, are in fact able to offer exemplary off-road traction, from sand or desert tracks to the deepest mud, while at the same time guaranteeing excellent resistance to abrasion, cuts, and tears so frequent in off-road use. All this together with excellent handling on asphalt, and very incisive wet performance thanks to the ability to interact in perfect synergy with the highly advanced riding assistance systems of the BMW R 1300 GS.

A peculiarity of the expedition was in fact the decision to tackle it with standard bikes and tyres, counting on the certainty of benchmark combined performance. It should be underlined, among other things, that this result was accomplished with 19-inch front and 17-inch rear sizes, which opens a new era in the adventure riding world.

An extreme challenge from both a technological and human point of view. The Nevado Ojos del Salado in fact subjected motorbikes, tyres and riders to a very tough test in extreme conditions. From over five thousand metres above sea level, to the cold and reduced atmospheric pressure, which required perfect electronic management of fuel-air mix as well as the reliability of each vehicle component. Metzeler tyres, on the other hand, had to cross terrains of all types, stoney ground, dirt roads, endless expanses of sand and with the unknown of discovering snow and ice on the route.

The participants in the expedition were required to make considerable physical and mental effort. Not only because the climb, which started from Bahia Inglesa, a town located near the port of Caldera on the Pacific Ocean, in the Atacama region, was completed in less than 24 hours, therefore requiring careful and tiring acclimatisation in the various base camps at different altitudes in the days preceding the undertaking before descending back to sea level for the departure. Above 5.000 metres you enter an inhospitable environment for humans. Temperatures are very low, around -10° C during the day with temperatures that could reach -20° C at night, and oxygen levels are rarefied.

The preparation of the expedition participants was treated with the utmost attention: all the riders underwent targeted medical tests and checks at the Kore University of Enna, in collaboration with the Provincial Health Authority of Enna. A simulation of the undertaking was also carried out in Sicily having as its backdrop Etna, the highest active volcano in Europe, in a symbolic twinning of this high-altitude simulation.

-

AGV Introduces the Limited Edition Guevara Motegi. (AGV/)AGV Press Release:

Introducing the Guevara Motegi, a limited edition helmet celebrating Izan Guevara’s first appearance at Motegi. The Guevara Motegi helmet is an exclusive release with only 2,000 units available, priced at $1,924.95.

Notable features of this replica helmet include the same graphics as Izan Guevara’s with the exception of other sponsors’ logos and visor components and accessories. The shell is crafted entirely from 100% carbon fiber, includes 5-density EPS, and was designed with a collarbone-safe profile. Additionally, it comes in 4 sizes and includes 5 front vents and 2 rear extractors. The graphics on the helmet pay tribute to the Spanish racer’s love for music and victory in the MOTO3 race.

For added comfort and customization, the 360° Adaptive Fit system allows riders to personalize the interior, tailoring the fit and thickness to suit the upper part of the head, nape, and cheek areas.

Features:

- 100% carbon fiber

- Metal Air Vents - Ensure aerodynamics and stability at high speeds

- Ultravision Visor - At 5 mm thick, this visor protects and allows 190° horizontal field of view / 85° vertical field of view

- 360° Adaptive fit

- Hydration system

- $ 1.924,95 USD

- For further details, please contact your preferred dealer.

-

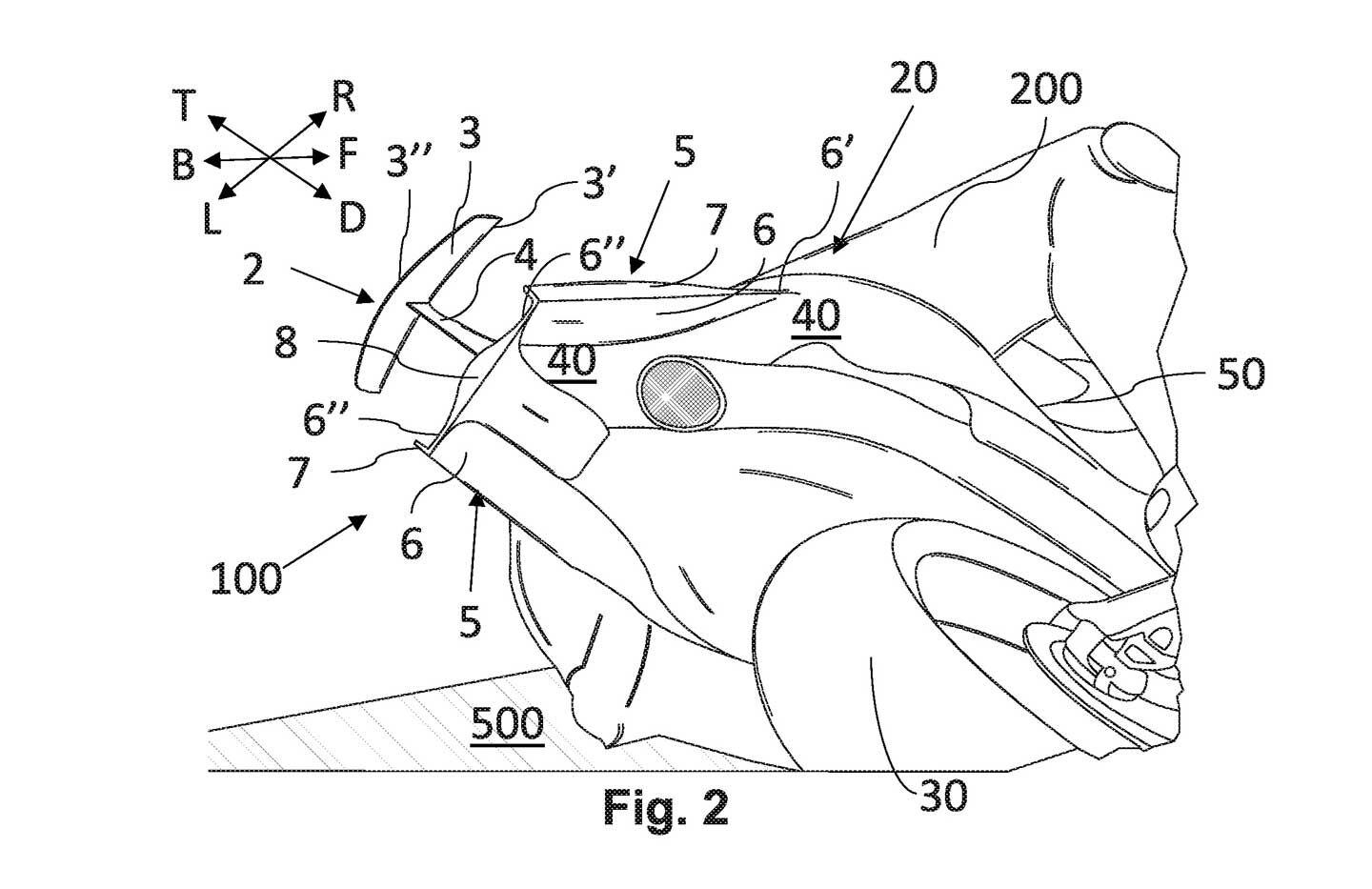

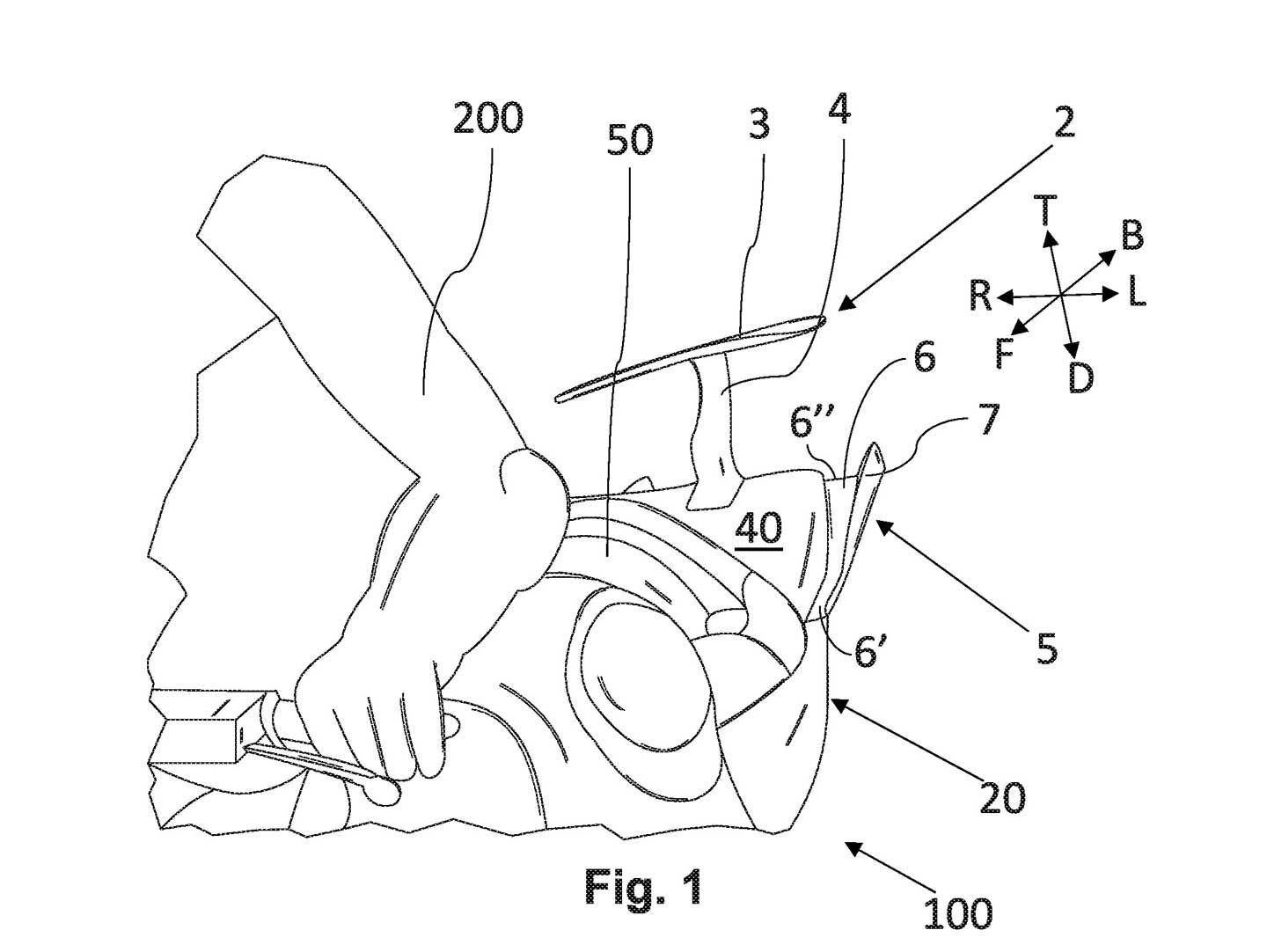

Aprilia has filed patents for the rear spoiler that was first seen back in 2022. (Aprilia/)Aprilia’s RS-GP MotoGP bike was the first to bring a racecar-style rear wing to the track back in 2022 and if the prototype 2024 racers seen at the end-of-season test in Valencia are to be believed, we’re going to be seeing the same on virtually every rival bike next year. And just as front winglets rapidly became a must-have styling addition on road-going sportbikes once they emerged in MotoGP the rear spoilers are likely to migrate to production models in the future.

That’s come a step closer with the publication of a patent application from Aprilia, describing the design and purpose of its racebike’s rear end but also making a clear indication that the same idea could be applied on the road, saying the idea “relates to ‘road’ or ‘street’ motorcycles” before going on to explain that the practical benefits really apply in racing. The patent illustrates the same rear winglet and spoiler combination that was first seen in 2022, and while it’s only just been published, the document was filed with patent authorities at around the same time.

Back in 2022, Aprilia made waves when it tested its rear spoiler for the first time. (Aprilia/)Ideas purely intended for racing are rarely the subject of patents. Partly because it means illustrating exactly how ideas work and explaining their benefits—not ideal in a highly competitive environment. After all, there’s no guarantee the patent will be granted, so filing an application could be simply giving your secrets away. Even if a patent is granted, it would be seen as unsporting to try to use patent law to prevent rivals from using the same idea in competition, and the proliferation of rear spoilers appearing on rival racers shows Aprilia isn’t trying to do anything like that. With that in mind, logically Aprilia’s patent application is intended to protect its idea in case the company decides to implement the same thinking on a production machine.

While rear spoilers are never likely to be game-changers for road bikes (even in MotoGP their benefits are still marginal, so the rear wings are often added or removed depending on specific circuits), carrying over the look of racers to the showroom is an essential part of the “win on Sunday, sell on Monday” idea that’s the whole reason companies plough money into their competition machines. With that in mind, it’s hard to imagine that we won’t see road-going superbikes with rear wings in the near future.

Will Aprilia’s spoiler make its way onto a production bike in the near future? (Aprilia/)What Aprilia’s patent does do is give a clear explanation of exactly what the rear wing arrangement achieves. Aprilia’s system is a little more complex than a simple wing, instead combining a pair of upswept winglets on the sides of the bike’s tail with a high-mounted spoiler on top. While the result looks a lot like the rear wings used on race cars to help plant them on the ground and corner at unimaginable speed, the motorcycle version’s benefits come on the straights. The downforce generated helps keep the back wheel on the ground, particularly during hard braking at the end of the straight, just as the rider tips into corners, when the rear wheel would normally be unloaded.

The document says: “…the spoiler allows an aerodynamic force to be created on the rear wheel. This force is effective above all during trail-braking, i.e., sudden braking, and is such as to reduce bouncing of the rear wheel, improving the grip of the bike and thus facilitating entering the corner. Moreover, the greater load that is created on the rear end of the motorcycle is useful in undulating straight stretches, such as a downhill stretch, in which the motorcycle reaches a speed of around 350 km/h [217 mph] and would tend to lose grip.”

Honda’s latest CBR1000RR-R SP production bike comes with updated aero, otherwise they wouldn’t be allowed in Superbike racing. (Honda/)Although Aprilia doesn’t currently compete in WSBK—its 1,099cc V-4 engine is too large for the current regulations and the company hasn’t yet followed Ducati’s lead and created a homologation-special, 999cc version to duck under the 1,000cc limit—it’s clear that a patented rear wing design, used on a streetbike, could give an edge in production-based racing. WSBK allows winglets provided they’re the same as those on the showroom versions of bikes, and we’re already seeing companies tweak their road bikes to improve those winglets. Honda’s 2024 updates to the CBR1000RR-R SP, for instance, include winglet changes that can only really be a benefit at the highest level of racing. Aprilia’s patent application covers itself in the event that it wants to put the aero thinking into production, and follows on from a patent in 2022 that described other aero tricks of the RS-GP. With the RSV4 superbike well overdue for a significant revamp, don’t bet against some of the concepts from Aprilia’s most successful MotoGP bike yet trickling down to the showroom.

-

Better than the best has arrived in another ASEAN nation with up to four variants and a ton of fanfare.

-

KTM is deep into final testing on its new 390 Adventure, which will likely be a 2025 model. (Bernhard M. Hohne/BMH-Images/) When KTM finally took the wraps off its next-generation 390 Duke earlier this year it was immediately clear that a new 390 Adventure sharing the same improvements would be hot on its heels. And here it is, spied testing in near-final form as KTM puts the finishing touches on a bike that takes a much more serious approach to off-road riding than its predecessor.

As before, the new 390 Adventure shares its platform with the similarly powered Duke, but since the Duke now has a new engine and chassis, those parts are filtering through to the Adventure in the near future. Let’s start with the engine. The latest design is dubbed LC4c, mirroring the name of the larger LC8c parallel twin used in the 790 and 890 models. As with previous KTM engines, the “LC” means Liquid-Cooled and the “4″ denotes the number of valves, but the extra lowercase “c”—a new addition for the single-cylinder in the 2024 390 Duke—means “compact.” While the “390″ element of the name is unchanged, the new engine clocks in at 399cc, up from 373cc for the previous version, with the extra cubes courtesy of an increased stroke, up from 60 to 64mm, while the bore is unchanged at 89mm.

On the heels of the recently announced 390 Duke, the 390 Adventure will share much of that bike’s mechanicals from the engine to the frame. But the new Adventure gets an upright Rally-inspired fairing, a 21-inch front wheel/tire combo, and wire-spoked wheels. (Bernhard M. Hohne/BMH-Images/) In the 2024 390 Duke, the new LC4c puts out 44 hp, up from 43 hp, while torque rises from 26 to 29 lb.-ft. Not huge increases, but the spread of performance is improved by the longer stroke, bringing the power peak down from 9,500 rpm to 8,500 rpm. KTM isn’t likely to give the 390 Adventure a substantially different tune, and that extra grunt may be even more useful in the off-road-style model than it is in the Duke roadster.

For 2024, the LC4c engine has also become the basis of new 250cc and 125cc singles in some markets—we get the 250 in the US—both with a similar bottom end but a more compact, SOHC cylinder head instead of the 390′s performance-oriented DOHC design, reducing weight, component count, and cost at the expense of some outright performance. There’s a good chance the same smaller-capacity engines will also find their way into Adventure models like the one spied here for markets where there are advantages to the 125cc or 250cc capacities, whether in terms of taxes or licensing.

The new 390 Adventure looks far more off-road ready than the current model. Note the smooth-sided swingarm, which differs from the current 390’s deeply braced unit. (Bernhard M. Hohne/BMH-Images/) Like the engine, the next-gen 390 Adventure’s chassis is pulled across from the 2024 390 Duke. It’s still a steel trellis design, but completely reworked for revised rigidity and weight. For the Duke, KTM added a cast aluminum subframe, but it’s not clear from these images whether the Adventure will follow suit. One prototype spotted—appearing to be an older one—had a subframe of square-section tubing, while the more finished-looking version is encased in bodywork.

When it comes to suspension, the Adventure veers away from the Duke’s design, and the next-gen bike appears to have a more serious approach to its off-road capabilities than the existing 390 Adventure. Where the current model uses a 19-inch front wheel, the new bike clearly has a 21-incher, allied to high-mounted front fender instead of the existing bike’s tire-hugging design. They are wire-spoked wheels, of course—a change from the cast alloys that are standard on the base 390 (though the US market only gets the 390 Adventure SW at the moment, with spoked wheels)—further emphasizing the off-road intent. The suspension will be from WP, as always, but the alloy swingarm loses the external bracing that’s been a constant presence on previous generations, favoring a cleaner (and easier-to-clean) shape.

There’s updated styling throughout, of course, with KTM’s new family face in the form of stacked headlights surrounded by a separate, coffin-shaped arrangement of LED running lights. We’ve already seen the 2024 990 Duke and the new 1390 Super Duke R Evo adopt this style. The lights are set into a more conventional front fairing than the current 390 Duke, with a tall, upright screen that has the Dakar-style rally-raid look that’s increasingly popular in the class. The screen extends around the headlight, forming the entire upper front fairing and giving a close resemblance to KTM’s real Dakar challenger, the 450 Rally.

We’ve seen in recent years that KTM is moving away from the traditional route of launching all its new models in one hit, trickling them into the market when they’re ready for production. So, while the next-gen 390 Adventure is sure to be called a “2025″ model, that doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll be waiting a full 12 months before it’s ready to be unveiled.

-

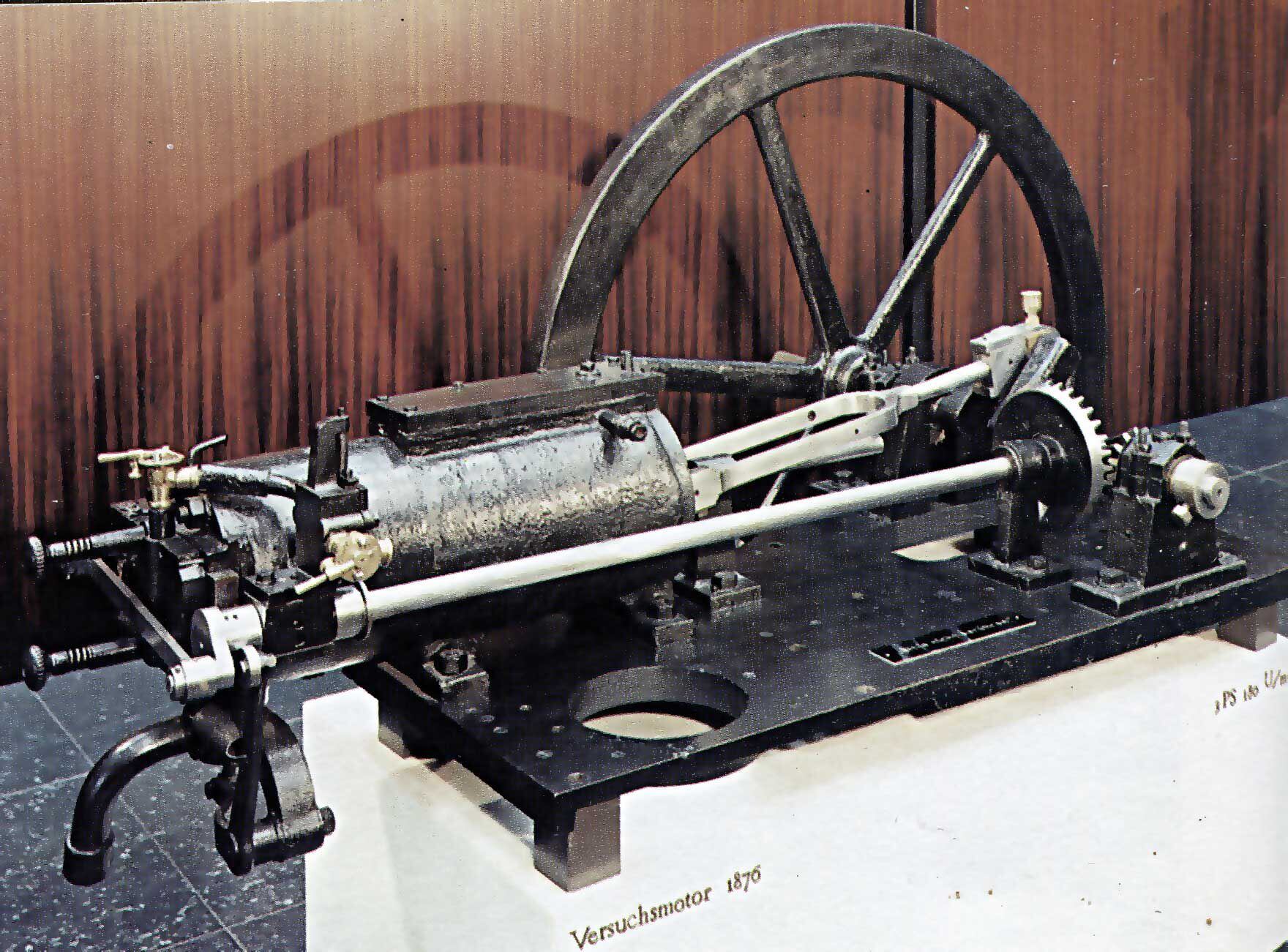

Kevin Cameron has been writing about motorcycles for nearly 50 years, first for <em>Cycle magazine</em> and, since 1992, for <em>Cycle World</em>. (Robert Martin/) The four-stroke spark-ignition internal combustion engine, invented by Nikolaus Otto in 1876, was a big step forward for transportation because it was small, light in weight, and could operate on fast-evaporating gasoline fuel. Its underlying principle is something very simple and familiar to us: Adding heat to a gas raises its pressure. Find a way to let that pressure act against a load and you have the elements of an engine.

Nikolas August Otto. (Public Domain/) On a clear day, the sun heats the land and the air above it, raising its pressure. The heated body of air expands, becoming wind. We know this is an “engine”—a device capable of doing work—because high winds uproot trees and blew Dorothy and Toto to Oz.

In the steam engine—which had been the dominant form of heat engine during the 19th century—water is heated inside a sealed container by burning fuel under it. Sufficiently heated, water becomes a gas and, being in our example confined inside a sealed container, its pressure rises.

If we make a cylinder, closed on one end and containing a close-fitting but movable piston, we can cause the piston to move quite forcibly by admitting steam to that cylinder. The expansion of the steam drives the piston, which can be connected to a load.

Because rotary motion is present in many kinds of machinery, a way was found to convert the back-and-forth motion of the piston to rotary motion. The simplest way is to link the piston to a rotating crank. One end of this link, or “connecting rod,” is hinged to the piston, and the other end is bored to fit over the “handle” of the crank (called the “crankpin”). One end of this “connecting rod” moves in a straight line with the piston, while its other end moves in a circle with the crank. A flywheel is usually added to make these motions smooth and continuous.

To keep this motion going we need some simple “housekeeping” functions: valves—one that will admit steam to the cylinder when the piston is nearest the cylinder’s closed end, and another that will release the expanded steam once the piston has been pushed to the far end of the cylinder. Mechanism is provided to open and close these valves in such a way as to repeat this power-producing cycle indefinitely.

The “choo-choo” sound of a steam locomotive is the intermittent outrush of spent steam from the working cylinder.

When inventors of the mid-to-late 19th century looked at a steam locomotive, its largest elements were the cylindrical boiler, many feet in length, and the firebox at one end. The parts converting expanding hot, high-pressure steam into mechanical power—the steam cylinders at the front of the engine, with their long connecting rods extending to drive the road wheels through crank action—were a small fraction of the whole.

Inventors asked themselves, “What if we burn the fuel inside the cylinders themselves? Then we’d have no need for the boiler or firebox.” The result would be smaller and lighter, perhaps enough so to power road vehicles.

Throughout the 19th century steam engines burned solid fuels—the coal that powered England’s Industrial Revolution, the wood that drove river steamers in the still-young United States—could not be burned inside cylinders.

But there was a brand-new fuel that could be: city-illuminating gas. The reduction of iron from its oxide ores required carbon, but at first, coal couldn’t be used because it contained a lot besides plain old carbon. Coal was therefore roasted in large retorts in the absence of air to become coke, which worked well in iron smelting. Roasting coal evolved gases and liquids that were also combustible. Lights burning this coal gas were much brighter and cleaner than oil lamps, so major cities were quickly plumbed to deliver this gas to streetlights, households, and businesses.

Inventors saw that this gaseous fuel could be ignited by spark or flame, and after 1860 many proprietary gas engines were created. They were feeble because the inventors, their minds prisoner to steam ideas, were trying to make engines that would produce a power stroke on every revolution of the crank. This forced them to try to fit too many functions into too little time, resulting in little power.

Nikolaus Otto, working in Germany, designed an engine which provided a separate piston stroke (a move from one end of the cylinder to the other) for each of the necessary four functions. As in the case of the steam engine, the stored kinetic energy of a flywheel kept operation smooth and continuous.

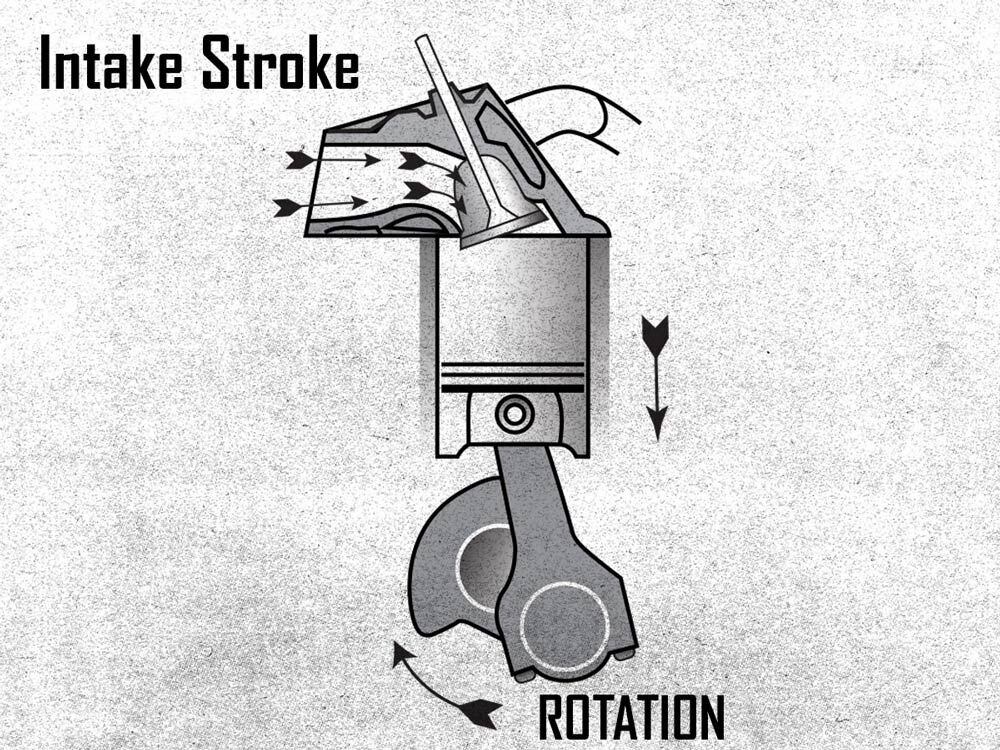

1) Intake: A valve in the head (closed end) of the cylinder opens and the piston moves away from the head. A combustible mixture of air and fuel rushes in from a mixing device (carburetor).

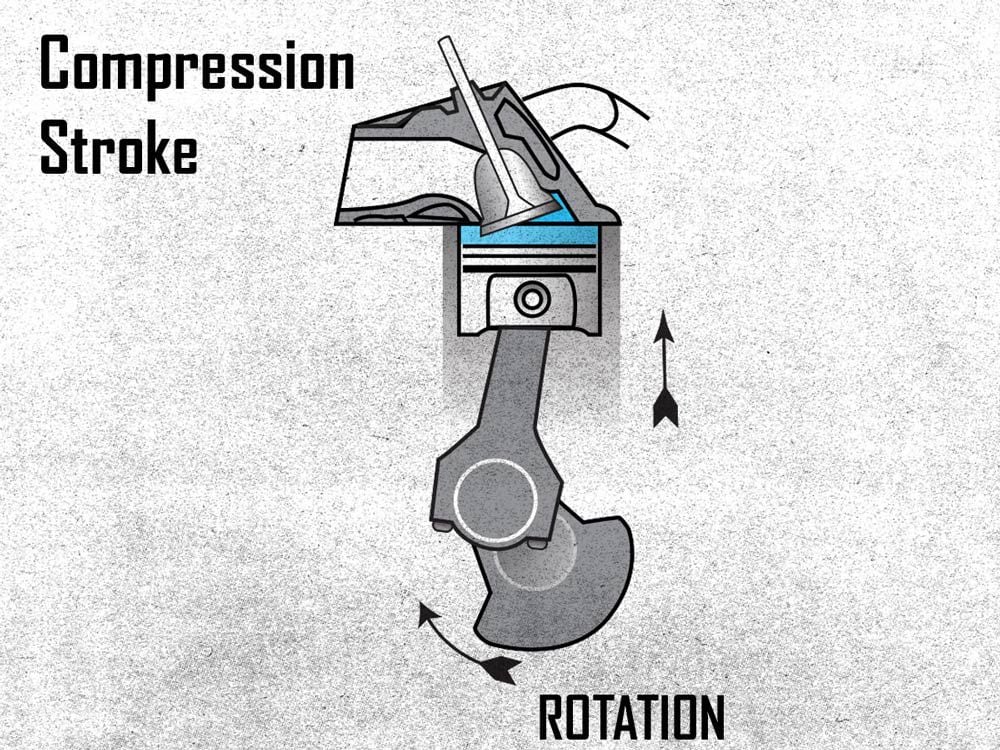

Intake Stroke. (Illustration by Robert Martin and Ralph Hermens/) 2) Compression: The intake valve closes and the piston is driven back toward the head, compressing the gas-air mixture in the cylinder.

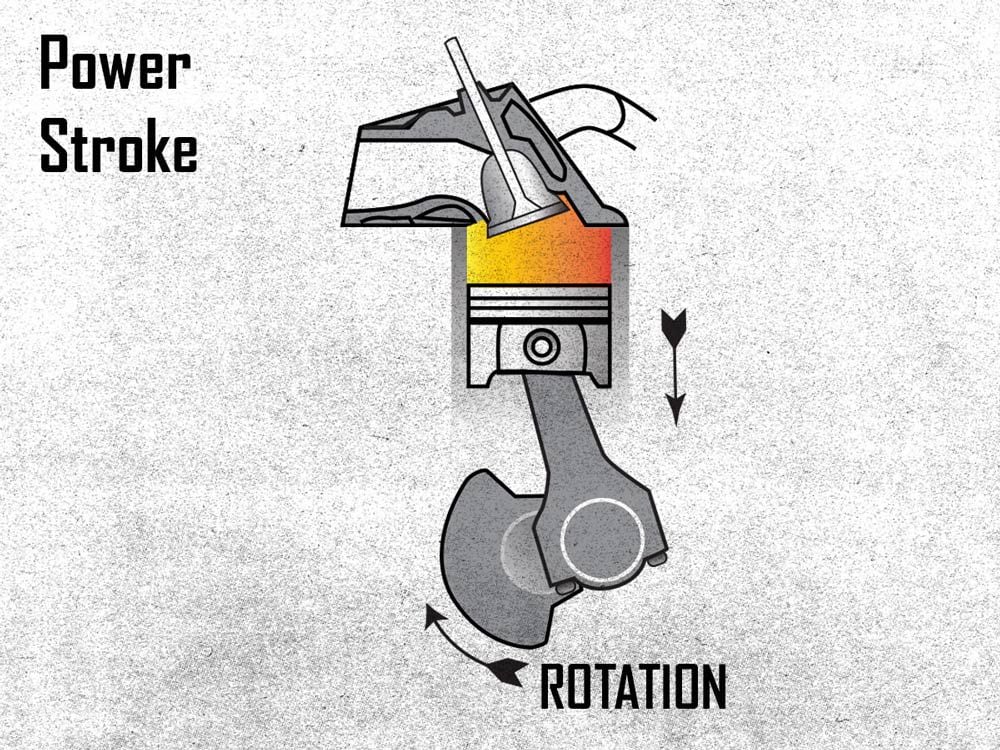

Compression Stroke. (Illustration by Robert Martin and Ralph Hermens/) 3) Power: The compressed mixture is ignited by some means while the piston is close to the head. Mixture combustion releases heat, greatly raising the pressure of the combustion gas. That pressure, transmitted through the piston to the connecting rod, spins the crankshaft.

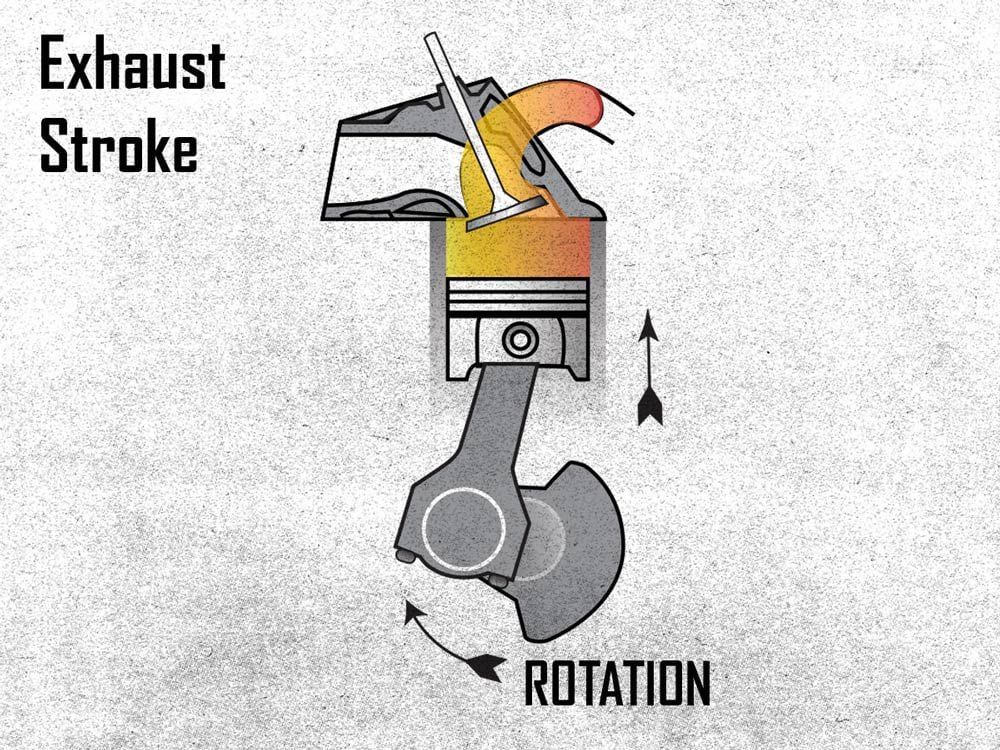

Power Stroke. (Illustration by Robert Martin and Ralph Hermens/) 4) Exhaust: As the piston approaches its far point, an exhaust valve in the head opens, releasing the expanded combustion gas into an exhaust pipe. As the piston rises toward the head, it pushes residual combustion gas out of the cylinder.

Exhaust Stroke. (Illustration by Robert Martin and Ralph Hermens/) The cycle repeats.

Because Otto provided a separate and dedicated piston stroke for each of these functions, they were highly effective.

Unfortunately, Otto had chosen the degree of compression (No. 2 above) to be quite high, so that when his experimental engine fired for the first time, it did so with great violence. He was shaken by this. Fortunately, his wife Anna was present. She assured him he would feel better after dinner and a night’s sleep, and would surely solve any problems the following morning.

Mrs. Otto was proved correct, and the Otto Four-Stroke Cycle continues to be the dominant prime mover for motorcycles, cars, and light trucks to this day—147 years later.

Each of these four functions deserves a separate explanation to follow soon.

Otto’s 1876 four-stroke engine. (Wikimedia Commons/) -

Like its limited-edition Lamborghini predecessors, Ducati’s latest collaboration with a VW Group stablemate, in this case Bentley, has just been unwrapped. (Ducati/) Ducati has been part of the vast VW Group for more than a decade now so it’s surprising we haven’t seen more tie-in products over the years. But after two hugely successful Lamborghini-branded limited editions—the Diavel 1260 Lamborghini launched in 2020 and the Streetfighter V4 Lamborghini from 2022—Ducati has unveiled its first cooperation with Bentley in the form of the new Diavel for Bentley and the even more exclusive Diavel for Bentley Mulliner.

The “standard” Diavel for Bentley model is mechanically identical to the Ducati Diavel V4, but features all-new styling that complements the Bentley Batur. (Ducati/) Bentley is, of course, another VW-owned company, sitting alongside Lamborghini and Porsche as the group’s halo manufacturers. Ducati sits in a similar position, though it’s VW’s only motorcycle company, so crossovers between the brands make a lot of sense. After all, the wealthy customers who buy Lambos and Bentleys might well have a penchant for motorcycles, while a Lamborghini- or Bentley-badged Ducati—even if they’re expensive in two-wheeled terms—is a low-cost way of getting a brand-new vehicle wearing either of those badges for the well funded.

Like the previous Lamborghini tie-in bikes, the new Ducati Diavel for Bentley models will be made in strictly limited numbers and have visual changes that extend well beyond a mere paint job and some bolt-on bits. Given the huge prices being asked for the bikes—more than double the cost of a standard Diavel V4—you’d expect some exclusivity, and that’s what you get.

Related: Ducati Announces Ducati Unica Customization Program

Although subtle at first glance, the bodywork, wheels, and styling have been redesigned with a collaboration between Ducati and Bentley’s styling teams. (Ducati/) The standard Diavel for Bentley—it seems wrong to call it the “base” model—will be limited to 500 examples and its styling has been created as a joint project between Ducati Centro Stile and Bentley’s own design team. It takes its cues from the $2 million Bentley Batur, an ultra-limited-edition super coupe with a 730 hp, twin-turbo W12 engine, coach-built in a run of just 18 cars. Every panel on the bike is new, with Batur-derived elements included in the redesigned air intakes, which mimic the car’s two-tone grille, and the seat, which features a combination of black Alcantara over a red lower layer. The front fender and headlight cowl shapes borrow from the hood of the Batur, with distinct ridges running along them, while the tail is claimed to be inspired by the rear of the car. The side panels, cowling the radiator, are also reshaped, and virtually every part that isn’t finished in the Scarab Green paint (a Bentley color) is left in bare carbon fiber, the material that all those new body parts are made of.

An exclusive Alcantara seat with Bentley badging for the rider and a removable cowl for the passenger seat is included. (Ducati/) Even the exhaust is redesigned, with a new cover that once again borrows ideas from Bentley cars, and the seat and tail—which comes with both a single-seat cowl and a removable passenger pad—are reshaped. Underneath all that are new forged aluminum wheels that have the same spoke pattern as the Batur. Despite all this, the bike’s mechanical parts, including the 1,158cc V-4 engine, the suspension, brakes, and electronics, are identical to the standard $26,995 Diavel V4.

Unique to the Diavel for Bentley bikes are the wheels which mimic the spoke pattern on the Batur. (Ducati/) While anyone with a big enough bank balance can rush to get an order in for one of the 500 Diavel for Bentley bikes in Scarab Green, an even more exclusive option is restricted to existing Bentley customers. Called the Diavel for Bentley Mulliner, which takes its name from the legendary coach builder that was absorbed into Bentley decades ago. Just 50 examples will be made, each tailored to their owner’s desires when it comes to the color of the bodywork, seat, front brake calipers, carbon parts, and wheels. Most buyers will, presumably, opt to make their bikes match their cars for a perfect pairing in the garage.

For those with even deeper pockets, 50 Diavel for Bentley Mulliner editions will be available for $90,000 and allow the customer to choose all the details. (Ducati/) Both the standard Diavel for Bentley and the Mulliner version will come with a certificate of authenticity, the removable passenger seat, a cover, and an engraved plaque bearing the bike’s number in the limited-edition run. There’s also the option to buy matching clothing in the form of a “jet” helmet and a jacket in colors to complement the bike’s.

What limited-edition $70,000 motorcycle is complete without a matching helmet? (Ducati/) All this comes at a cost, of course, with the 500 “standard” Diavel for Bentley bikes coming in at $70,000. The Mulliner version will set customers back a cool $90,000. Despite the high prices, the bikes are likely to sell out fast. Last year’s Streetfighter V4 Lamborghini models, made in slightly higher numbers (630 standard bikes at $68,000 and 63 “Speciale Clienti” versions at $83,000 for existing Lambo owners) were said to be sold in a matter of hours after order books opened.

Front view of the Ducati Diavel for Bentley. (Ducati/)

Ducati’s Diavel for Bentley alongside the Bentley Batur. (Ducati/) -

Vespa is now valued at 1 billion euros. (Vespa/) Vespa is a unique case in the history of two-wheeled motor vehicles in more than one way. First, Vespa is the only model—now a make—that survived through all the crises that have battered Italian industry since its inception, keeping its image and personality almost perfectly intact from its days in 1946. Piaggio built its financial fortune on the success of Vespa, not only then but even now—almost 80 years later. Vespa brand value has grown no less than 19 percent in the past two years and now just broke the 1 billion euro valuation barrier, according to global brand consultant and valuator Interbrand.

Vespa is the main pillar of the whole Piaggio Group’s financial health with a 30 percent turnover increase just in 2022. In the past couple of decades, Piaggio managed the Vespa brand and related models with a very sharp policy that mixed substantial under-the-skin technical improvements to well-placed styling touch-ups—both to the top-range GTS and the smaller Primavera. This policy has made the Vespa even more iconic in that it retained all its classic, nostalgic appeal while maintaining functionality, reliability, and safety.

Recently the iconic status of Vespa received an official acknowledgement by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) that stated that the design of Vespa cannot be imitated, being perfectly recognizable all over Europe. This sentence closes a 10-year legal battle between Piaggio Group and Chinese Zhejiang Zhongneng Industry Group that had put into production their ZNEN scooter that was a total copy of the Vespa.

Vespa has won a legal battle regarding its design and its being copied. (Vespa/) In 2014 the EUIPO (European Union Intellectual Property Office) recognized the uniqueness of the Vespa design and acknowledged it as a trademark. But in 2018 Zhejiang Zhongneng Industry Group won the cancellation of the Vespa trademark in court, having acquired a stronger position on the European scene after purchasing the Moto Morini brand. The EUIPO reverted its previous decision and gave the Chinese company free hand to produce and sell its ZNEN scooter.

Vespa’s iconic shape is once again a trademark in Europe. (Vespa/) Piaggio Vespa fought back and went to the CJEU to once again register Vespa design as a trademark. Now the EU court has reverted the judgment in favor of Piaggio Vespa and the ZNEN scooter cannot be imported and sold anywhere in Europe.

In 2020, Vespa had won another similar quarrel at EUIPO against another Chinese imitator, Chen Huang, that also had put into production copies of the one and only Vespa. This last one is a big success for Vespa that might fight for its iconic uniqueness also in other markets.

-

1

1

-

-

Ask Kevin Cameron (Cycle World/)A reader has written, “One of the technical aspects of modern MotoGP I find most confusing is the use of so-called rear squat devices to accelerate out of corners. While watching a recent MotoGP practice session I heard Simon Crafar waxing poetic over the advantages of keeping the center of gravity lower with the rear squat device. It made me wonder how we got here.

“When I learned to ride a bike it was explained to me that all motorcycles are made with a swingarm pivot explicitly designed to have anti-squat behavior on acceleration, as though squat were the enemy. But now MotoGP engineers seem to think squatting during acceleration is advantageous. What caused the thinking to change from squat = bad to squat = good? And if squat is good, do you really need a squat device, or could you just change the swingarm pivot to get rid of that pesky anti-squat behavior? Would squatting on acceleration ever be good for street bikes as well, or is there some reason this is only desired in racing?”

Confusion regarding the role of squat can be resolved by seeing that two different circumstances are involved.

Rear Squat

Rear squat—and indeed any reduction in center of gravity height—during acceleration while upright allows the rider to accelerate a bit harder before hitting the “wheelie limit” set by front wheel lift.

Rear squat allows the rider to accelerate harder by lowering the CG. Wheel lift limit is increased as the rear squats. (Ducati/)Rear squat while accelerating, still leaned over in a corner takes weight off the front tire, reducing its ability to steer the motorcycle, and so causing it to run wide. This is corrected by setting the swingarm pivot at the correct height, allowing drive chain tension to generate a lift force that cancels acceleration squat.

Motorcycle racing is naturally experimental and pragmatic: Whatever works to solve a specific problem will be adopted, provided it does not produce harmful side effects or cause itself to be banned because it works well.

Dragsters are built low to raise their wheelie limit as high as possible. Back in 1973 one of our shop mechanics was trying to drag race his new Kawasaki 750 H2 Triple but couldn’t get anywhere because the front end kept popping up, forcing him to choose between wasting the run by chopping the throttle or letting the bike flick over backward. I suggested he try lowering the bike, which he did, by about 3 inches, front and rear. Next Sunday his launches were strong and his time slips were no longer embarrassing.

But when Honda attempted to improve the corner exit acceleration of its 1988 NSR500 GP bike by lowering it and giving it a near-horizontal swingarm that actually encouraged squat, a nasty side effect appeared. During corner exit the accelerative transfer of weight off the front tire and onto the rear tire reduced the front tire’s ability to steer. The bike therefore ran wide, forcing the rider to throttle back, resulting in getting passed by those pesky Yamahas.

Someone at Öhlins did an analysis of this and issued a four-page memo on how to use swingarm pivot location to prevent squat-and-push. Remember that this applies only to a motorcycle that is accelerating while still leaned over and turning. By the early 1990s the word on this had gotten around such that production bike models homologated for World Superbike were being manufactured with adjustable-height swingarm pivots to allow teams to legally give their riders bikes whose pitch attitude did not change when they applied throttle to accelerate while still leaned over. Squat-and-push could now be controlled or eliminated.

The “Holeshot Device” Appears

Motocross has been a prolific source of two-wheeled innovation. Suspension travel has increased in MX to the point at which bikes are so tall that wheelies seriously limit their starting-line acceleration. Someone decided to try compressing an MX bike’s front suspension by several inches, and holding it down with a kind of latch. The latch was equipped with a spring that would flip it out of engagement at the first sharp bump or brake application. This was given the name “holeshot device” because it could on a one-time basis raise the wheelie limit enough to win the drag race to turn 1.

Naturally, this was tried in roadracing—still on a one-time-use basis. Being first into turn 1 is so important that soon, everyone’s bike had the holeshot device. As noted above, it works by reducing CG height, thereby making the bike more “dragster-like” (by making wheelies less easy).

Lowering Both Ends of the Bike

Soon one or more crew chiefs, riders, or engineers asked this question: If the front suspension holeshot device works during the straight-line acceleration from the start to the braking point for turn 1, what if we lowered and latched down the rear suspension as well? Naturally, because this further lowered the bike’s C of G, it further increased acceleration capability.

The next step had a rule standing in its way: What if we built a device to lower the front and rear suspension every time the bike is accelerating or braking upright in a straight line? The rule forbids use of external electrical or hydraulic systems to power such ride height changes.

Ride height changes in MotoGP must be triggered by the rider, not automatically. (Andrea Wilson/)Upon approaching corners such a system could return to normal ride height to provide cornering clearance.

Making Variable Ride Height Self-Powered

To circumvent the rule, someone remembered the “Nivomat” constant ride height suspension units for touring bikes. Nivomat’s internal self-pumping action (driven by suspension movement) allowed it to maintain normal ride height despite the added weight of a passenger and/or luggage. Soon MotoGP bikes could be seen squatting at front and rear to increase straight-line acceleration or braking, then rising to normal height to provide cornering clearance when leaned over.

It is currently forbidden by rule that such systems operate automatically, so the rider must trigger each ride-height change manually. A future ban of variable ride height is anticipated.

-

They might not have much power, but there are several points in their favor, especially for beginners.

-

The 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 is a holdout in the world of ever-increasing rider aids. (Jeff Allen/) Traditional 600cc inline-four sportbikes are a diminishing breed. They are now being displaced by models with half the cylinders that are less complex to produce. As Kevin Cameron once wrote, “Everybody’s doing it, and that now includes Suzuki.” In his article he discusses the new 776cc parallel twin used in its new GSX-8S naked bike and 800DE adventure bike. Now there’s the GSX-8R on the way. But, for now, its four-cylinder sportbike lineup has not yet disappeared.

The 2023 Suzuki GSX-R has been virtually unchanged since 2011. (Kevin Wing/) The middleweight sportbike category is being introduced to twin-cylinder engines that have been adapted to suit public roads more than twisty racetracks. Manufacturers—such as Yamaha with the YZF-R7—have followed the trend of adapting the already existing platform to fit their sportbike platform. With the introduction of Suzuki’s GSX-8R parallel twin and the waning popularity of supersport racing, does the GSXR-600 still make sense?

Suzuki’s GSX-R600 gives an analog experience at the track and on the road. (Jeff Allen/) In an era of overwhelming electronics, TFT displays, throttle-by-wire, intrusive ABS, and reworked geometry, Suzuki’s GSX-R600 manages to stay relevant without conforming to the new norm. The 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 ($11,699) is the epitome of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Utilizing the same platform since its major overhaul in 2011, the Japanese middleweight sportbike is a favorite among racers, stunt riders, and enthusiasts alike.

There is something charming about its raw nature. A crisp mechanical throttle, a simplistic dash, no electronic intervention, and a familiar 599cc inline-four—the GSX-R600 is only limited by its rider.

The contour of the tank and bodywork provides a flat surface area for the rider to grip the bike. (Jeff Allen/) A liquid-cooled 599cc DOHC four-cylinder engine is wrapped in a twin-spar aluminum alloy frame with fully adjustable suspension. Showa’s race-developed Big Piston Fork and single shock provide plenty of performance both on track and road. At the binders, shedding speed on the front end is achieved through radial-mounted four-piston Brembo Monoblock calipers with 310mm discs. The rear brake system utilizes a single-piston Nissin caliper. Suzuki Drive Mode Selector (S-DMS) is the only switchable electronic feature on the 600, providing the rider with the option between two maps for road or track conditions.

The 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 weighs 419 pounds on our automotive scales. (Kevin Wing/) On CW’s Dynojet 250i dynamometer, the GSX-R600 produced 102.9 hp at 13,520 rpm and 44.0 lb.-ft. of torque at 11,580 rpm. Typical for middleweight inline-fours, this Gixxer engine produces its best power in the top-end. But its relatively lackluster bottom-end has benefits as well. During commuting miles its soft low-end torque provides a smooth and consistent linear pull that effortlessly carries the bike down the road with a delightful exhaust rumble.

To pick up the pace, keep the rpm high. On twisty canyon roads and mountain passes, the 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 does its best work after 8,000 rpm and makes usable and direct power all the way up to its 15,000 rpm redline. Trying to keep up with torquey twins or triples? Work the six-speed gearbox hard and don’t be afraid to tickle the rev limiter.

Suzuki's GSX-R600 is fitted with a simple dash utilizing an analog tachometer and digital speedometer and gear position indicator. (Kevin Wing/) In tight, switchback sections staying in second gear and running the 599cc inline-four all the way up to its rev limiter before chopping the throttle and working the Brembo brakes yields the best results. Constantly keeping the revs on the boil gave the punchy acceleration needed to “get out of the hole.”

On twisty backroads, the Suzuki prefers to be revved out from one corner to the next. (Kevin Wing/) When the road has enough of a stretch where a shift was required, the tight and crisp six-speed gearbox provides a direct change that is easily accomplished without the clutch, just a quick chop of the throttle. The lack of a quickshifter added to the Suzuki’s raw charm. Similarly, its predictable power delivery off the apex eliminated any reservations stemming from the lack of traction control.

Despite the lack of modern electronic rider aids, Suzuki’s GSX-R600 is stable and confidence inspiring when on the side of the tires. (Jeff Allen/) On the racetrack, it’s no different. The 599cc inline-four will punish the rider’s lap times if the revs drop into the lower half of the tachometer. Former AMA Superbike racer and CW test rider Chris Siebenhaar noted, “The GSX-R600 does start finding its legs and has a smooth steady pull in the upper rpm.”

The dyno graph may be the best explanation of all. Below 8,000 rpm, the GSX-R600 produces little power and torque. The curve is linear, offering a smooth engine character when pulling away from a light, but once the bike surpasses the midrange, this middleweight sportbike really comes alive. At 102.9 peak horsepower, the GSX-R600 is by no means a monster, but its high-revving character and linear powerband give the rider a large rpm window in the upper range to work with when connecting corners in the canyons or on the racetrack.

2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 Dyno Chart. (Robert Martin/) Another clear indication of this bike’s purpose, other than the engine, is the ergonomics. Being a traditional sportbike, the ergonomics are heavily influenced by track performance. And, of course, the street comfort is sacrificed. Rider triangle is tight and places the rider over the front of the motorcycle. Spending time commuting on the bike, one inevitably has to sit up and back on the bike and take your left hand off the bar to alleviate any discomfort.

The top-end has enough power to lift the front wheel over a crest. (Jeff Allen/) In the twisties, where the road is constantly transitioning from left to right, those aggressive ergonomics create more work, requiring the rider to transition from one side of the bike to the other. At street speeds, it’s easy to covet the wide bars and upright seating position enjoyed by naked-bike riders. On long sweeping corners that were not quickly followed by a direction change, the Gixxer 600′s ergonomics reward the rider when hanging off the side of the bike. But on quick transitions, the clip-on handlebars do generate more work.

Off the racetrack, the rider triangle feels cramped and less comfortable than a standard motorcycle. (Kevin Wing/) On mountain roads, the Suzuki GSX-R600′s suspension settings are busy and jostled the rider. Every bump in the road is amplified. After reducing compression damping, the GSX-R instantly gained more confidence at the front end. This adjustment allows the front wheel to follow the ground more smoothly and not transfer so much feedback into the chassis. In the hard braking zones off a fast straight, the fork drops further into the stroke and puts more weight on the front end, generating more front tire grip which maximizes the braking potential without the aid of ABS. The racetrack provided similar results; Siebs said: “Suspension on the GSX-R600 is firm and supportive from the time you clamp on the binders, all the way through the corner.”

The Brembo Monoblock calipers and 310mm rotors provide consistent braking performance. (Kevin Wing/) The Suzuki requires some work from the rider to set up for a corner, but once it is on the side of the tire, it stays planted and is stable until the exit. Siebenhaar explained, “It is planted, stable, and settles some of the rider’s movements. Around the fast bends the Suzuki tracks straight as an arrow; it bends into corners with a very smooth and linear manner.”

On the side of the tire, the GSX-R600 is very composed. (Jeff Allen/) Although the Suzuki GSX-R600 may be long in the tooth compared to bikes such as the newly updated 2024 Kawasaki Ninja ZX-6R, its raw charisma is its appeal. Advancements in motorcycle technology are a good thing. Safety equipment keeps the rubber side down more often than not and having gadgets to play with allows the rider to make a bike their own. But with so many interferences and safety nets, motorcycling is losing some of its analog experiences.

Shows Big Piston Front Fork is fully adjustable with rebound (Ten) on the left and compression (Com) on the right. (Kevin Wing/) “My favorite thing about the Suzuki is the raw feeling of the riding experience, starting with the motor it feels like there is more connection from the throttle to the rear wheel,” Siebenhaar said.

As the automotive manual transmission was edged out by the automatic, it was clear the general public preferred the car doing the work for them. However, today car enthusiasts fret at the possibility of never rowing through another manual transmission. In a way, the Suzuki GSX-R600 is the same. Its lack of updates and innovative technology are exactly what make it so much fun to ride.

The ergonomics of the GSX-R600 are more suitable for racetracks than parkways. (Jeff Allen/) Jumping from a bike with cutting-edge technology to a bike that is basically unchanged from 2011 reintroduces the connection between rider and machine without IMUs and wheel sensors intervening. Switching gears, managing traction, and rolling on the throttle with precision creates an engaging and satisfying experience on the 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600.

The flat seat provides a large platform to move around the cockpit of the GSX-R600. (Kevin Wing/)

The Suzuki GSX-R600 gas tank holds 4.5 gallons of fuel. (Kevin Wing/) 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 Specs

MSRP: $11,699 Engine: DOHC, liquid-cooled, 4-stroke inline-4 Displacement: 599cc Bore x Stroke: 67.0 x 42.5mm Compression Ratio: 12.9:1 Transmission/Final Drive: 6-speed constant mesh/sealed chain Cycle World Measured Horsepower: 102.9 hp @ 13,520 Cycle World Measured Torque: 44.0 lb-ft @ 11,580 Fuel System: Fuel injection w/ SDTV Clutch: Wet, multiplate Engine Management/Ignition: Electronic ignition (transistorized) Frame: Twin-spar aluminum Front Suspension: Inverted telescopic fork, fully adjustable Rear Suspension: Link-type, single shock, fully adjustable Front Brake: 4-piston radial-mount Brembo calipers, floating 310mm discs Rear Brake: Nissin 1-piston caliper, disc Wheels, Front/Rear: Cast aluminum; 17 in./17 in. Tires, Front/Rear: 120/70-17 / 180/55-17 Wheelbase: 54.5 in. Ground Clearance: 5.1 in. Seat Height: 31.9 in. Fuel Capacity: 4.5 gal. / 4.2 gal. (CA model) Cycle World Measured Weight: 419 lb. Contact: suzukicycles.com -

1

1

-

-

The ADV and dual-sport non-profit is raising money with some pretty sweet travel experiences and training opportunities.

-

Royal Enfield’s newest adventure bike looks to lock horns with the lightweight industry veterans.

-

Francesco Bagnaia is one of only three MotoGP riders to win back-to-back championships. (Ducati/)Francesco “Pecco” Bagnaia is the two-time MotoGP champion who lives next door. The Ducati factory rider is the classically good guy you don’t expect. Introverted, he loves the stability of his family, the company of his fiancée Domizia Castagnini, and a close circle of friends. He’s the guy every mom would love as their daughter’s husband. But—and there is always a but—with his helmet on and visor down, the 26-year-old Italian rides over 200 mph. Pecco is a paradox for the best in the class. This is a portrait of the 2023 MotoGP world champion who won with authority and back to back the title in Valencia.

A Victory in Style

“I won the title as I have always dreamt: winning the race,” Bagnaia confessed. Both challengers had the same bike: Ducati’s GP23 that proved to be the best bike on the grid. There was no room for excuses, and the best racer won. With Jorge Martín out on lap 6, betrayed by his own fire to win, Bagnaia pushed till the very last corner to win and shout to the world that he made it. Winning is tough, repeating is even harder. In the history of the modern MotoGP only Valentino Rossi and Marc Márquez won back to back, and Pecco has entered by right into this exclusive elite.

A Tribute to the NBA

As Rossi used to do, Pecco celebrated by paying homage to his beloved sport: He dribbled a basketball and then dunked it in the basket, wearing three big golden NBA-style rings that correspond to his three titles (including his 2018 Moto2 success).

Although he didn’t need to, Bagnaia closed out his championship season with a win. (Ducati/)Number One

“As a rider, we don’t look too much at statistics, but it feels good to write history. This Is the happiest moment of my life,” he stated sitting comfortably on a chair and looking at the race results. Following the tradition of the old-school riders, this winter Bagnaia was brave enough to choose to put the No. 1 on the fairing of his Ducati, contrary to the Doctor who has always kept his iconic 46.

Heir

Bagnaia grew up at Rossi’s Ranch, leaving his hometown Chivasso, near Turin, to learn from the best. As coincidences do not exist, Pecco started to make the difference as a racer the second half of the 2021 season, the last for Rossi. “Winning the Valencia GP in 2021 on the same Sunday when Valentino competed for the last time in the premier class, was an incredible emotion,” Pecco recalled. The nostalgia for the closing of an era together with the feeling that there was a passing of the baton was in the air. On Sunday the traditional fracas, the Spanish fireworks, were red, with the flags at the racetrack turning slowly, slowly from neon yellow to Ducati color.

The Man Versus the Rider

Like the sun and the moon, the Doctor and Bagnaia have two different personalities. “Sportingly, I owe so much to Valentino. I learned a lot, but I never made the mistake of trying to copy him,” Pecco confessed. “What Rossi told me at the start? simply to remain calm.”

Perhaps the secret of his success lies in the skill to remain himself, despite Ducati’s astronomical pressure to get the title back to Borgo Panigale in 2022 and to repeat this year. Shy and introverted, Bagnaia is conquering with his simplicity the hearts of MotoGP fans—the orphans of Rossi looking for a new hero to connect with.

Bagnaia has gained many fans in his time in MotoGP—not because of a flashy style or boisterous attitude, but because he is himself always. (Ducati/)At the garage, Pecco is described as a precise, meticulous, and generous guy. As a rider they say he is very fast, strategic, and technical. As Rossi did, Bagnaia spends a lot of time with his chief mechanic studying the telemetry and the strategies—because in order to push at the limit he needs to have everything under control.

Determination

Under contract with Ducati on the eve of the 2018 season, before even conquering the Moto2 title, Pecco earned Borgo Panigale’s trust. “Because of his determination and ability to give his best with the means at his disposal without complaining or making excuses,” Ducati Corse team manager Paolo Ciabatti said. Being a hard worker and a keen observer has led him to be simply Pecco Bagnaia: the good guy on top of the world.

The Fear to Overcome

The most difficult moment this season was his massive and scary crash in Barcelona.

“Barcelona’s crash marked me a lot,” Bagnaia explained. “It was so scary, especially when Binder’s bike passed over my leg. Pain and fear are in front of my eyes recalling this moment. I was determined enough to jump on the bike in Misano one week later. I gritted my teeth as I couldn’t move my knee, and I succeeded to lose only 14 points instead of 37 versus Martín. In the following races I suffered even more—even though I didn’t show it; in this second part of the season I lost the speed, struggling on Friday and being not so competitive in the sprint. We still don’t know why, but we need to find a solution, and improve for next season. Fortunately, I’m Sunday Racer.”

Bagnaia recognizes that he must become better on Friday and Saturday if he wants to remain a champion. (Ducati/)2024

“Compared to last year, now I am aware that I am more competitive, and I am able to manage the situation, even if I made some mistakes during the season,” Pecco said. “In 2022 I fought versus Quartararo, this year I knew that my main rival would have been on a Ducati. Sharing the data also with Martín and the other riders has some pros and cons, especially when you are so close in the championship.”

He added, “For next year we need to raise the bar. We cannot afford to struggle at the beginning of the race weekend. Despite all, I think we deserved to win. Except on time, we were leading for the whole season.”

Family

Those who know Pecco well undoubtedly point to his secret: the stability that comes from his family. His older sister Carola is his assistant at the garage, skilled to calm him when he is nervous, his parents, and even his grandmother Luciana. His family is his home, despite the fact that he lives in Pesaro, with his future wife Domizia and his dog Turbo. You might not believe it, but at home he is the one at the stove. He prepares a perfect carbonara and he would love to join the TV show MasterChef one day, because he is also a champion in the kitchen.

-

Kawasaki is one of three manufacturers still producing 600cc inline-four sportbikes. In fact, it continues to develop them as well. The ZX-6R just received an extensive overhaul for 2024. Before riding the new bike, we wanted to throw the previous generation (2013–2023) Kawasaki Ninja ZX-6R on our Dynojet 250i dynamometer for what will likely be the last time.

Kawasaki’s Ninja ZX-6R has always had a slight displacement advantage over its competition. With the bike utilizing a 636cc inline-four DOHC 16-valve engine with 38mm Keihin throttle bodies, the unorthodox engine displacement is an attempt to provide more usable low- and midrange power for casual street riding. The 2023 model also features two power modes, three levels of Kawasaki Traction Control (KTRC), and a quickshifter (up only). And of course, the chassis is fitted with track-ready components. The 2023 Kawasaki Ninja ZX-6R has a fully adjustable 41mm Showa Big Piston Separate Function Fork, a fully adjustable gas-charged shock, and dual Nissin Monoblock four-piston calipers up front.

2023 Kawasaki Ninja ZX-6R Dyno Chart. (Robert Martin/)Before loading the Ninja onto the Cycle World dyno, we placed it on our automotive scales and recorded a wet weight of 432 pounds. On our in-house Dynojet 250i dynamometer, the 2023 Kawasaki ZX-6R produced 108.4 hp at 13,200 rpm and 45.8 lb.-ft. of torque at 10,900 rpm. For reference, the 2023 Suzuki GSX-R600 produced 102.9 hp at 13,520 rpm and 44.0 lb.-ft. of torque at 11,580 rpm. The ZX-6R’s extremely linear power delivery and flat torque curve is routine for this class. Although the increased low-end torque is noticeable, like any 600cc sportbike, revving it to the moon yields the best results.

-

1

1

-

-

Just before I went on a biking holiday I got the Furygan Odessa jacket which, as it turns out, makes for a great touring jacket as it is so versatile and accommodates various weather conditions as I found out

Check out my review here:https://www.webbikeworld.com/furygan-odessa-vented-ladies-jacket-review/

https://www.furygan.com/produit/odessa/?lang=en

The post Furygan Odessa Vented 3-in-1 Ladies Jacket Review appeared first on BikerKaz.

-

Aprilia Racing and Trackhouse Together in MotoGP (Aprilia Racing/) Aprilia Racing Press Release:

Aprilia Racing has signed a three-year agreement with US outfit Trackhouse, already a major player in the NASCAR motorsport championship. Captained by former racer Justin Marks, the American team will bring the RS-GPs to the track as an Independent Team. Confirmed are riders Miguel Oliveira and Raùl Fernandez, in their second season riding the Italian prototypes.

A partnership that will see Aprilia Racing take charge of all technical aspects, collaborating closely with Trackhouse Racing on track and taking care of development during the season, through a dedicated structure that represents an important step forward in Aprilia’s MotoGP project.

MASSIMO RIVOLA - CEO Aprilia Racing

”We are happy and proud to welcome Trackhouse into the Aprilia Racing family. What they have been able to build in a very short time in NASCAR is an extraordinary presentation card, which anticipates the potential of this partnership. This is thanks to Justin Marks and his team, whom I got to know through my long-time friend PJ Rashidi, and with whom we were immediately in sync both in terms of technical ambitions and marketing and communication developments in such an important market as the US. Our commitment will increase significantly, a responsibility we gladly take on because, I am sure, it will allow us to grow even more”.

-

Triumph has shortened the Scrambler 1200 X to make it more accessible for more riders. (Chippy Wood/) You either get Triumph’s 1200 Scrambler or you don’t. You either relish its uncompromising, slightly old-fashioned approach to its role as a dual-purpose retro bruiser, or you find its steepling seat height and lack of adventure-bike comforts and sophistication too much to contemplate, especially on dirt.

Triumph has recognized this fact because the new and significantly rethought 2024 Scrambler 1200 X is the Hinckley factory’s olive branch to those who find themselves drawn to the Scrambler’s unquestionable charisma while being slightly intimidated by its size and bulk.

A lower seat height makes coming to a stop (on or off-road) less worrisome. (Chippy Wood/) With shorter-stroke suspension and a lower seat height, the 1200 X is more accessible and easier to live with day to day and, with $1,150 sliced off its price tag at $13,595, is considerably cheaper than the Scrambler 1200 XC it replaces. Some may question why Triumph has replaced the older bike’s Brembo M50 brakes, Showa fork, and piggyback Öhlins rear shocks with less aspirational Nissin stoppers and Marzocchi suspension units front and back, but 1200 X is about giving more customers access to the Scrambler franchise. A lower seat, a better price, plus an electronic upgrade that adds lean-sensitive ABS and traction control to the table all point to a more pragmatic, road-focused package.

The more off-road-biased Scrambler 1200 XE continues unabashedly, tall and rowdy and up for a day in the dirt as ever. It also receives a raft of updates, many of them shared with the X. Crucially, though, the differentiation between the two 1200 offerings is now much clearer than it was. And the X is the Scrambler for everyone.

Related: How To Choose The Right Dual-Sport Motorcycle

Suspension duty is now handled by Marzocchi units, front and rear. (Chippy Wood/) Engine-wise, both 2024 machines use the High Power version of Triumph’s liquid-cooled 1,200cc parallel twin. Claimed peak power and torque of 89 hp and 81.1 lb.-ft. are unchanged, but those peaks now arrive 250 rpm earlier than before at 7,000 rpm and 4,250 rpm. There’s a new, single 50mm throttle body, revised exhaust headers to broaden the spread of torque, and a new heat shield arrangement for the high-level exhaust to help reduce the temperature around the rider’s right leg.

That electronics refresh brings cornering traction control and five riding modes: Sport, Road, Rain, Off-Road, and Rider Configurable. Cycle World enjoyed perfect autumn weather conditions on the test in Spain, which allowed, on asphalt at least, toggling exclusively between Road and Sport modes. There isn’t a massive step in performance or throttle response between the two. Whichever you choose, the X responds smoothly and urgently, pulling strongly from just above tick-over, before stomping through its wonderful midrange and delivering more than enough zip at the top-end.

With less ground clearance, footpegs on the Scrambler 1200 X now touch down more often than the previous XC model. (Chippy Wood/) Without riding the old XC and new X back to back it’s not overly apparent that more torque is on tap in the lower rpm, but the new bike, like the old, is awash with delicious big-Bonnie grunt. Short-shifting becomes the norm on any ride and I rarely revved the X beyond 5,500 rpm as there’s simply no need. Peak power is at 7,000 rpm but you can make brisk progress using a maximum of just 5,000 rpm.

Harnessing all this meaty goodness is the same (and unchanged for 2024) steel cradle frame used in both the outgoing XC and updated XE, but with entirely new suspension. In place of the XC’s fully adjustable 45mm Showa USD fork and Öhlins piggyback rear shocks come Marzocchi units, front and rear. Fork diameter remains at 45mm but is nonadjustable while the rear shocks get spring preload adjustment only. Crucially, both fork and shocks have reduced strokes, with travel shortened from the XC’s 7.9 inches at each end to just 6.7 inches.

Triumph Scrambler 1200 X Road Riding Impression

As soon as you settle on the 1200 X’s classy bench seat you feel the difference. Seat height drops from the XC’s 33.1 inches to 32.3 inches and is considerably lower than the new XE’s 34.3 inches. With an optional even-lower seat you can reduce that figure to 31.3. At 5-foot-7, just, I am one of those riders who’ve always been a touch intimidated by the 1200 Scramblers but Triumph has drastically changed all that by simply shortening the suspension travel, meaning I no longer have to plan where I’m going to stop in fear of not being able to touch the road. I am far more confident.

Triumph removed the “C” from the name while adding value and accessibility. (Chippy Wood/) For sure, the Marzocchi name may not exude the MotoGP raciness of the departed Öhlins goodies, but the Italian suspension specialists manufacture quality goods and in terms of real-world performance there is little lost.

On the brilliant twists and turns in the roads of Malaga, I never once felt the need to stop the bike and change the suspension settings. The pace was brisk, the roads flowing, and the feedback and support were spot on for a bike with a 21-inch-diameter front wheel. In fact, with its travel reduced by 1.2 inches, the suspension is better suited to the road, certainly less of a road/dirt compromise than the older XC. However ground clearance has been reduced, meaning the pegs do tickle the road on occasion. Heavier riders who ride hard will need added preload if they want any pegs remaining after a fast ride out.

While cornering ABS adds more safety and reassurance to the rider, there is no hiding the fact that the 1200 X has reduced braking power compared to the previous model, with smaller 310mm diameter discs (down from 320mm) and axial-mount Nissin calipers instead of the radial-mount Brembos M50s of the XC. On occasions, when braking hard into tight downhill hairpins, the usual, gentle brush of the lever with one or two fingers wasn’t enough; instead, a firm three-finger pull was required to get the X stopped.

Braking performance has diminished with the change to Nissan calipers and smaller-diameter discs. (Chippy Wood/) Another welcome update comes in the form of a single, circular dash, simple and easy to navigate, with optional Bluetooth. An underseat USB port and a foam-lined storage box keeps your smartphone tucked away safely with its battery topped up. A 70-item list of accessories is typically impressive, too, meaning you can, for example, transform your 1200 X into a tourer with factory luggage options offering 102 liters of total storage, including a 35-liter tail pack, or opt for off-road-biased rubber, fit crash protection and a bash plate, and head for the fire roads.

The circular dash is easy to navigate and has optional Bluetooth connectivity. (Chippy Wood/) Off-Road on the Scrambler 1200 X

Given the road-biased Metzeler Karoo Street tires fitted to the 1200 X, I don’t think Triumph was too happy that I took the new Scrambler for an unofficial off-road test. But so long as you’re not intending to hit the trails hard, or jump and bounce over rocks, then the 1200 X is still capable of enjoyable green lane sorties. With the TC deactivated, the X’s accurate fueling, balance, and accessible torque made it easy to slide the rear without inviting disaster. Should you get a little carried away, the ABS is designed to work off-road. However, do remember, despite now appealing to shorter riders, she’s still a heavy bike when ridden off-road; at 503 pounds it’s not a lightweight Scrambler as the name suggests.

Even with Metzeler Karoo Street tires the Scrambler 1200 X is capable of off-road travel on dirt roads. (Chippy Wood/) Verdict

Triumph has redrawn its big-cube Scramblers for 2024, producing two very different bikes in the 1200 X and 1200 XE. There is now a clear and better understood gap between the pair. By downgrading the spec and being realistic about their customers’ needs, Triumph has made the 1200 X easier to ride than the XC, which should widen its appeal to riders of all sizes.

For 2024, Triumph has made the ride on the Scrambler 1200 X easier for smaller riders. (Chippy Wood/) The X has nicely balanced, softly set, road-focused suspension that remains stable and planted when pushed. Power delivery is delightfully punchy and there’s that enhanced spread of gooey torque to shovel it past cars and out of turns. Its economy is good, with 50 mpg (USA) easily attainable, and service intervals are at 10,000 miles, meaning long-term running costs should be moderate. The 1200 X makes owning a big Scrambler cheaper, easier, and safer than before. And, for those of us lacking in height, more fun too.

Triumph’s Scrambler 1200 X prices at $13,595. (Chippy Wood/) 2024 Triumph Scrambler 1200 X Specs

Price $13,595–$14,095 Engine: SOHC, liquid-cooled parallel twin; 4 valves/cyl. Displacement: 1,200cc Bore x Stroke: 97.6 x 80mm Compression Ratio: 11.0:1 Transmission/Final Drive: 6-speed/chain Claimed Horsepower: 89 hp @ 7,000 rpm Claimed Torque: 81.1 lb.-ft. @ 4,250 rpm Fuel System: Electronic fuel injection w/ 50mm throttle, ride-by-wire Clutch: Wet, multiplate assist Frame: Tubular steel Front Suspension: 45mm Marzocchi USD fork, nonadjustable; 6.7 in. travel Rear Suspension: Marzocchi twin RSU, spring preload adjustable; 6.7 in. travel Front Brake: 2-piston axial caliper, dual 310mm discs w/ Cornering ABS Rear Brake: 1-piston floating caliper, 255mm disc w/ Cornering ABS Wheels, Front/Rear: Tubeless 36-spoke aluminum; 21 x 2.15 in. / 17 x 4.25 in. Tires, Front/Rear: Metzeler Karoo Streets; 90/90-21 / 150/70-17 Rake/Trail: 26.2°/4.9 in. Wheelbase: 60.0 in. Seat Height: 32.3 in. Fuel Capacity: 4.0 gal. Claimed Wet Weight: 503 lb. Contact: triumphmotorcycles.com -

One of the biggest design revolutions in MotoGP is aerodynamic downforce. (Andrea Wilson/) Anyone remember those heady days in the 1980s when it seemed as if revolutionary and far-out-looking forkless Grand Prix bikes were about to start winning races? Honda poured money into the GP program of the French Elf group, running Ron Haslam as its rider. In 1987 he was fourth in the 500cc championship.

That revolution did not take place. Each year, based upon rider feedback, the forkless front end was modified to improve it. And each year it looked less radical, and more like, well, a conventional telescopic fork.

Now we actually are in a design revolution, and unlike those forkless front ends of 40 years ago, this revolution is working. The first element is use of aerodynamic downforce to allow harder acceleration without either front wheel lift or electronic throttle cuts to prevent it. That one, in my opinion, is causing the recent rash of outstanding new lap records.

The second element is variable ride-height systems like those now available on Harley-Davidson’s Pan America and BMW’s R 1300 GS dual sport production bikes. For them, the systems exist to reduce seat height so average people can confidently hold up, when stopped, bikes made tall by long-travel off-road suspension. But in MotoGP, bikes have become tall to maintain adequate corner clearance as tire grip has increased, and this makes them wheelie more easily, limiting peak acceleration. Once the front wheel lifts, it becomes easier to lift it higher, making “pop-up” wheelies the enemy of strong drives off corners.

When the bike is at lean angle in corners, ride height is maximum, but when the bike is more upright, it can accelerate faster if “turned into a dragster” by lowering front and rear ride heights.

Electronically lowering front and rear ride height when maximum acceleration is needed is another big development for MotoGP in the recent past. (Andrea Wilson/) Yet as observed by Ducati management this past weekend, if you change too many things at once, there isn’t time in a racing season of 18 to 20 GPs to make it all work properly. Add to that the fact that these bikes are now very sensitive to small changes: If a rider can get the shapes of parts in contact with his body altered to just right, he can go much faster. Look at the extreme rider positions necessary with today’s tires and you understand how small changes could affect accurate control. We saw this with Jorge Lorenzo on Ducati: At the time, he sounded like “Mr. Hard-To-Please” but once the bike fit him well, he began to win races.

The above tends to prevent anything that’s really Buck Rogers from showing up at preseason tests. Instead, as so many riders listed, there were new aero, maybe new swingarms, a few chassis, and “engine and electronics updates.”

The first big news from the test—not exactly surprising—was that once Marc Márquez was on the Gresini Ducati instead of the Hondas he has ridden for so many seasons, he rose quickly to top time, then at the end of the day was fourth fastest. Even though surrounded by young hotties whose “hunger to win” is so often harped upon by pundits.

Maverick Viñales (factory Aprilia), who ended the day with quickest time, was as careful as the others not to say anything of real import: What did you test? “Not a lot of big things.

“…important to understand a few directions for the next year.”

His biggest need? “I’m looking for a bike that can brake late. Because I want something that’s good on the brakes but turns tight.”

Maverick Viñales ended the test with the quickest time. (Andrea Wilson/) Bikes that have the midcorner grip to hold a line tend to have more flexible chassis that act like suspension when leaned over, keeping the tires on the pavement rather than skipping through the air. But trying to brake really hard on a flexy chassis can provoke instability. MotoGP riders have learned to be vigilant when they feel the tires “moving around.”

He continued, “One of the main points to improve was the start, which we accomplished.”

Years ago Yamaha had this trouble, which was traced to a steep rise in the grip of clutch friction material as the clutch heated up during a start (you often see riders stopping on the circuit when practice ends, to make standing starts). That can make the clutch grabby rather than smoothly linear in engagement. Aprilia’s starting problem may very well have been something else, but this is one that’s documented. It is usual to replace clutch plates after one or at most two such starts to maintain predictable performance.

Yamaha and Honda have been “the sick men of MotoGP” in recent years, as the European makers embraced the new technologies while the Japanese teams hoped they might just go away (or be banned). The rather long and drooping nose of one Yamaha fairing carried a slotted airfoil in full-width Aprilia style, and the down-sloping “deck” into which was let the narrow rider’s screen has the aspect of a “dive plane, angled at 45 degrees. Ducatis also feature this relatively flat but angled “deck” around the windscreen. On other makes the nose is rounded rather than flat in this area.

Yamaha showed a full-width slotted airfoil on one of the 2024 testbikes. (Andrea Wilson/) Yamaha’s seat back was plain—no “stego-foils” projecting from top or sides like Ducati’s. The lower of the two exhaust pipes on the right-hand side appears recessed into the swingarm to pull it in out of the wind.

Álex Rins, newly on Yamaha, said, “In the morning I rode with the bike used by Quartararo in the race, grinding kilometers and trying to familiarize myself with all the devices. In the afternoon, however, I focused on aerodynamics. The technicians brought two new packages and one in particular I really liked for stability and grip.”

Marc Márquez was forbidden by the final days of his Honda contract from saying much, but did manage to grin and say “the grip is amazing” after riding the GP23 Ducati.

Marc Márquez let lap times do most of the talking. (Andrea Wilson/) Francesco Bagnia, the new and now two-time world champion, remarked that the new Honda looked “long, like the Ducatis.” This is interesting because Márquez tended in his winning years to prefer a shorter-wheelbase bike for its ability to immediately transfer weight to front tire in braking, rear tire in acceleration. On the other hand, Yamaha’s longer wheelbase was one of its distinguishing features back in Rossi’s prime, as it can be an element in the stability a bike needs to remain near peak grip all the way around long, fast corners. Think of the times the Honda men have remarked that their bikes were at disadvantage on circuits with corners of that kind.

Honda is at the moment using winglets at the sides of the fairing nose, Ducati style, as in that location air velocity has accelerated to flow around the bulbous nose, increasing potential for generating downforce. Aprilia and (now) Yamaha are using greater wing area (the Aprilia has a long chord) as a downforce strategy.

Joan Mir’s Honda looks very Ducati-like. (Andrea Wilson/) KTM team manager Francesco Guidotti made the usual limited utterance: “We are looking for small gains in electronics, aerodynamics, everywhere.

“We know our engine is strong and the (carbon) chassis is the first spec of the new technology; there are plenty of areas where we can still work.”

KTM rider Jack Miller said, “We are working hard to make a broader power range, tried a different traction control. We also tried a hand brake.

“We made a step with grip.”

KTM looked to make small gains. Jack Miller said the KTM made an improvement in grip. (Andrea Wilson/) Teammate Brad Binder said, “We didn’t have anything big or radical but we learnt a lot about what we did use.”

There are now roughly two months in which to select and refine hardware for the February test at Sepang in Malaysia. Success is not gadgets. It is being able to identify the most productive avenues of work, and choose those most able to be made ready in time.

Lap times are fun to look at, but mean little in this context. That’s because we have no idea what information each test object is aimed at generating.

Valencia Postrace MotoGP Test Times