Admin

-

Posts

7,486 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Store

Gallery

Community Map

Posts posted by Admin

-

-

Suzuki’s new teaser for its upcoming GSX-S1000 model reveals more modern, triple stacked LEDs leading the way. (Suzuki/)While other Japanese firms pump out new bikes at a breakneck rate, Suzuki operates at a steadier pace, so news that a new GSX-S1000 will soon be revealed—hot on the heels of the revamped 2021 Hayabusa—comes as something of a surprise.

The bike is the subject of a new teaser video from the firm that, as usual with such marketing tricks, is designed to give away as little as possible. It’s the usual format: darkened images, close-up glimpses, and a somewhat nonsensical slogan—in this case “the beauty of naked aggression”—which in any other context would seem a somewhat disturbing notion. However, there’s a fair amount that can be interpreted from the teaser as well as Suzuki’s recent trends in new model development.

The tagline likely refers to a more modern exterior redo of the existing GSX-S1000. (Suzuki/)While it’s tempting to imagine that Suzuki will go all-out on its next-gen GSX-S1000 and create a 200 hp Ducati Streetfighter V4 rival by stripping the fairing off the latest GSX-R1000, the reality is that the firm’s development pattern in recent years has been to cleverly reskin existing components and add a veneer of technology. We saw it with the Katana (which is, of course, GSX-S1000-based), and again with the V-Strom 1050. Even the new Hayabusa confounded expectations that the firm might have spent years developing radical technology for the bike; instead it carried over a refined and revamped version of the existing engine in a virtually unaltered chassis.

RELATED: GSX-S1000Z

Every indication suggests the same tactics will be applied to the GSX-S1000, and it’s a route that actually makes a lot of sense. For all the theoretical appeal of a super-naked derived from the latest GSX-R1000, the reality is that the existing GSX-S1000, with a 150 hp engine spawned from an all-time great, the 2005 GSX-R1000 K5, already has performance to spare on the road. Building a new version around the latest superbike’s variable valve timing engine and exotic chassis would inevitably increase price while offering only marginal benefits to the majority of customers in the market for such a bike.

A restyled fuel tank and tail seem likely, and the new gold-colored fork suggests there will be updates to the suspension as well. (Japanese Patent Office/)The Katana has already proven that the GSX-S1000′s bones can easily be clad in more attractive bodywork, and by covering the part of the market that wants a retro-styled machine, it opens the door for the GSX-S itself to be made into a more overtly modern-looking bike. That’s the “naked aggression” that Suzuki’s teaser is talking about, and even in a darkened room the glimpses of the new bike show a vast improvement over the rather dowdy and dated GSX-S1000.

Up front, triple stacked LEDs replace the oh-so-20th-century halogen headlight of the current model, and there are unmistakable, downward-turned winglets either side of the nose. Side panels jutting forward from the edges of the fuel tank wrap around the fork, almost meeting the headlight unit and acting as supports for those winglets. The overall effect should push the visual weight of the bike forward, with further assistance from a new fuel tank that’s angled to meld more smoothly into the seat. The tail, although largely hidden in the teaser, also appears to be restyled, and the new GSX-S1000 appears to lack the pointy-fronted bellypan of the current model, leaving the exhaust headers in clear view instead.

Technically, the changes aren’t likely to be vast. With luck we’ll get suspension updates, and the teaser certainly shows a revised fork with a gold-colored coating instead of the current bike’s black finish unit. The brakes appear to be unchanged, but since the GSX-S1000 already has Brembo radial calipers, that’s no bad thing.

No doubt there will be updates to the bike’s electronics, and of course the fact that there’s a new GSX-S1000 is a sure indicator that the faired GSX-S1000F is also likely to be right behind it in the queue for revisions. Full details of the new bike are coming on April 26, so there isn’t long to wait. If you were about to pull the trigger on a rival model like Honda’s CB1000R, it might be worth holding back just to check what Suzuki has in store.

-

Hello Stu smith,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

A successful retro standard motorcycle balances nostalgia and performance, style and rideability. Now, 54 years after the first V7 and 13 years after the first modern recreation, Moto Guzzi has released the fourth generation of that modern iteration of the V7 with an all-new engine and chassis. With iconic styling and all of the quirks and character that Guzzi is known for, the nostalgia is there. But has the classic-styled bike’s performance been updated enough to stay competitive with this quickly growing genre of motorcycles?

The 2021 Moto Guzzi V7 Stone has a starting MSRP of $8,999. (Moto Guzzi/)The biggest update in this model is the new engine, designed to meet Euro 5 emissions standards and drawing on elements of Guzzi’s previous V9 and V85TT but unique to this model. Overall design of the engine is not radically different from previous versions of the bike, maintaining the two-valve-per-cylinder pushrod configuration. Thanks to the new larger displacement, we see a 25 percent increase in power over previous models, a claimed 65 hp at 6,800 rpm and 53.8 pound-feet of torque at 5,000 rpm. The crank has been re-balanced, and friction has been reduced to limit the torsional rotating effect so present when revving previous V7 models. That pull-to-the-right while revving is still there, for the nostalgic; it’s just reduced to a minor sway rather than a tug to one side.

Our first ride test took place in the California desert outside of Palm Springs—a great destination for both wide open and twisty roads. (Moto Guzzi/)Power output of previous V7 models was notably underwhelming, so the increase in engine performance is something that we welcome eagerly, as it makes the new bike a much more capable machine. Most of that power comes on after the 3,000 rpm mark, but the engine produces tiring vibration through the handlebars at the same point; this does not smooth out until it reaches peak torque at 5,000 rpm. The cable-driven throttle provides a direct, connected feel, but fueling is abrupt with the initial twist; it takes slow, precise throttle application to achieve smoothness. The clutch lever is springy and the feel is very vague, making it hard to detect the engagement point based on your hand alone. The combination of abrupt fueling and lack of clutch feel can lead to a bit of lurching, especially if you have the traction control switched off.

The 2021 V7 Stone with the Centenario version behind it. (Moto Guzzi/)At one point in our test ride, I was carving through some mountain roads while staying in the higher revs above 6,000 rpm, near peak horsepower. I closed and reopened the throttle quickly and was greeted with a pulsing effect from the fuel injector that upsets the chassis. Thinking it may have been a fluke, I tried this on three different motorcycles and found that it was consistent and repeatable.

An all-new digital gauge on the V7 Stone, matching the shape of the new headlight. (Moto Guzzi/)Guzzi has developed a new chassis to house the new powerplant, though it’s a similar tubular steel layout with similar weight distribution to previous models. The rear shocks are larger with longer travel, and the swingarm is now larger and reinforced, with a new bevel gear on the shaft drive to better handle the higher torque output.

Handling on the V7 is neutral and easy, but push it too hard and the soft suspension will remind you how this bike likes to be ridden. (Moto Guzzi /)The V7 easily drops into turns and now has the power to effortlessly pull out of them. Low-speed handling is neutral and easy. Going straight down the highway, the ride is smooth and stable. Only when pushing the bike, heavily leaning through turns at speed, did I find the shortcomings of the suspension. Both the fork and the shocks are a bit soft in both spring rate and damping, resulting in bouncing through bumpy turns and forcing me to slow down. Rebound is adjustable on the rear, which did help to slow the bobbing; the front is nonadjustable.

Subtle Moto Guzzi branding hides throughout the bike, like the eagle silhouette that serves as a daytime running light. (Moto Guzzi/)A four-piston Brembo caliper grips a 320mm disc to stop the 18-inch front wheel, and while it takes a fair squeeze of the lever, there’s good feel for precise application. The rear two-piston caliper and 260mm disc are more than adequate as well; present, but not too grabby, with decent feel at the foot lever.

The new bike comes in three models. As in previous years, the V7 Stone wears matte black paint with aluminum six-spoke mag wheels, a digital gauge cluster, and LED lighting, available for $8,999. For 2021 only, celebrating the 100th anniversary of Moto Guzzi, a Centenario version of the V7 Stone is available for $9,190, sharing all the same functional components as the V7 Stone but with a two-tone livery and a brown seat. Lastly there is the V7 Special, with glossy paint, dual analog gauges, and spoked wheels, as well as machined cylinder cooling fins and a brown swingarm for $9,490. Each 2021 model has the special 100th anniversary logo on the front of the fender.

Brembo four-piston calipers provide excellent stopping power up front. (Moto Guzzi/)While the V7′s styling is very similar to what we’ve seen on model after model here, that is a good thing. It’s still undeniably attractive. The line from tank to seat, the knee indents, and subtle Moto Guzzi branding details throughout make it simply a great-looking standard. As each bike shares the same engine, tires, and chassis, there is room for up-spec’d models to be released later on.

In true “Stone,” fashion, the base model V7 Stone comes only in matte black. (Moto Guzzi/)The gearbox on the new V7 is essentially a five-speed with an overdrive. Gears one through five feel great and are truly all you need for practical use, with fifth gear pulling 80 mph at 5,100 rpm. Sixth gear seems like a bit of a mileage play, as 4,000 rpm will only have you going 70 mph and vibrates too much for smooth highway cruising.

Each V7 produced for 2021 will come with the special 100th anniversary logo on the front fender. (Moto Guzzi/)The retro standard category is growing quickly, with offerings from OEMs all over the world. From Triumph’s updated Bonneville line to Royal Enfield’s wildly successful $6,000 twins, there is something to fit every level of performance and most budgets. The Guzzi V7′s strengths are in its classic Guzzi character and styling, but when you view performance and pricing next to others in the class, it becomes hard to justify the purchase based on those factors alone.

Moto Guzzis have always been funky motorcycles, bikes out on the fringe. They’re a choice for the rider who doesn’t want a Harley or a Triumph, but something more unique, Italian, and not seen quite as often. Thanks largely to the engine configuration, they’re quickly recognized by those in the know, and their classic styling is universally appreciated. It’s a friendly bike that isn’t too loud, too big, or unwieldy. It’s not trying to be a racebike. it’s just a simple, good-looking machine. Ride it within its capabilities and it will be good to you for many years to come.

At 6-foot-4, editor Morgan Gales was surprised to find the V7 is a comfortable fit with his knees below his hips and body upright. (Moto Guzzi/)Gear Box

Helmet: Hedon x Bike Shed Heroine

Jacket: Alpinestars Brera Air

Pants: Tobacco Selvedge Riding Jeans

Gloves: Lee Parks Design

Boots: Bates Fast Lane

2021 Moto Guzzi V7 Stone

MSRP: $8,999 Engine: Air-cooled, transverse V-twin, pushrod; 2 valves/cyl. Displacement: 853cc Bore x Stroke: 84.0 x 77.0mm Transmission/Final Drive: 6-speed/shaft Claimed Horsepower: 65 hp @ 6,800 rpm Claimed Measured Torque: 53.8 lb.-ft. @ 5,000 rpm Fuel System: EFI w/ 38mm mechanical throttle body Clutch: Dry clutch Frame: Double cradle tubular steel frame Front Suspension: 40mm fork; 5.1 in. travel Rear Suspension: Dual Kayaba shocks, preload adjustable; 3.9 in. travel Front Brake: Brembo 4-piston caliper, 320mm disc Rear Brake: Brembo 2-piston floating caliper, 260mm disc Wheels, Front/Rear: Cast aluminum mags; 18-in. / 17-in. Tires, Front/Rear: 100/90-18 / 150/70-17 Rake/Trail: 26.4°/4.2 in. Wheelbase: 57.1 in. Ground Clearance: 6.1 in. Seat Height: 30.7 in. Fuel Capacity: 5.5 gal. Claimed Wet Weight: 481 lb. Availability: Spring 2021 Contact: motoguzzi.com/us_EN/ -

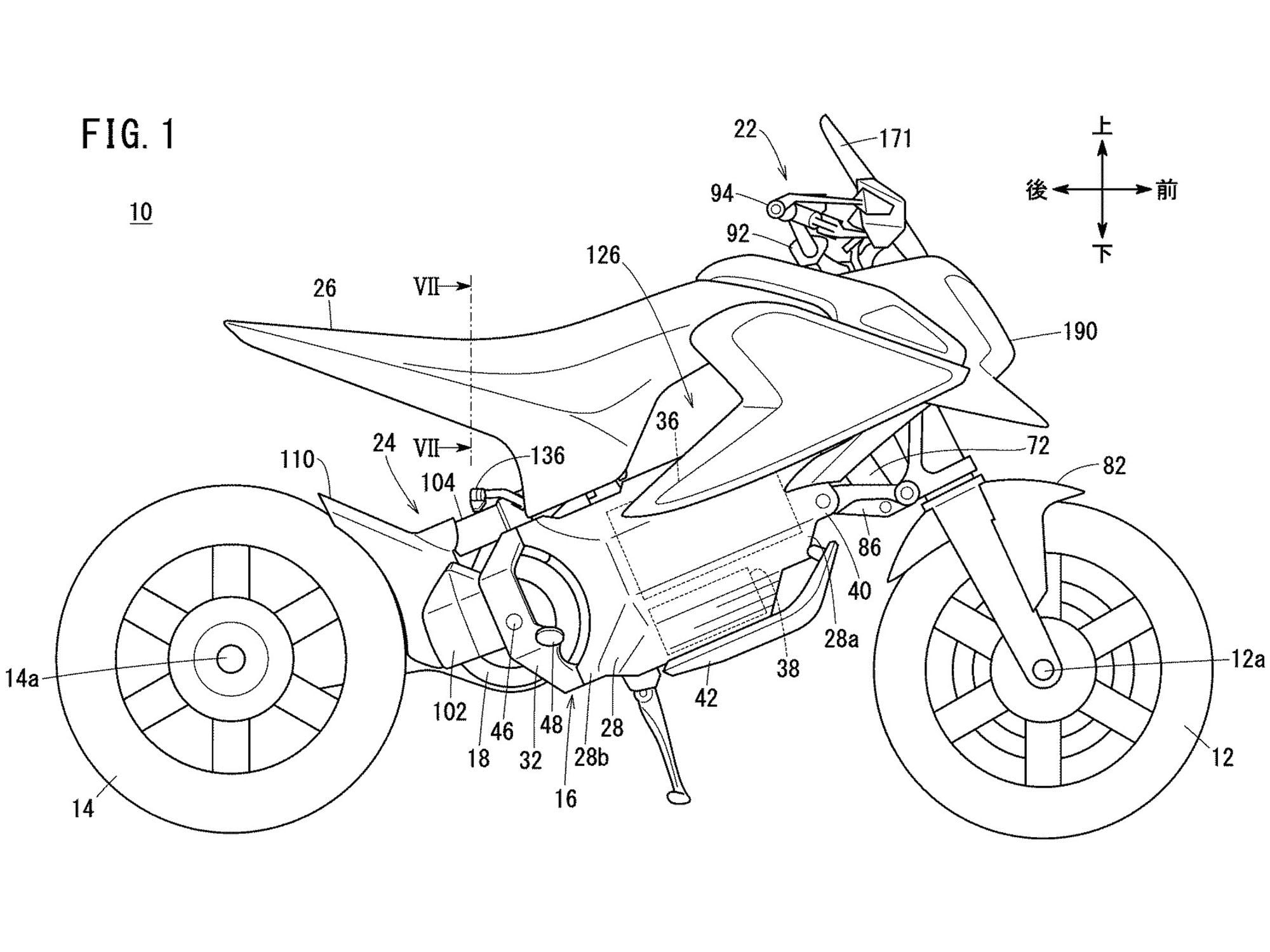

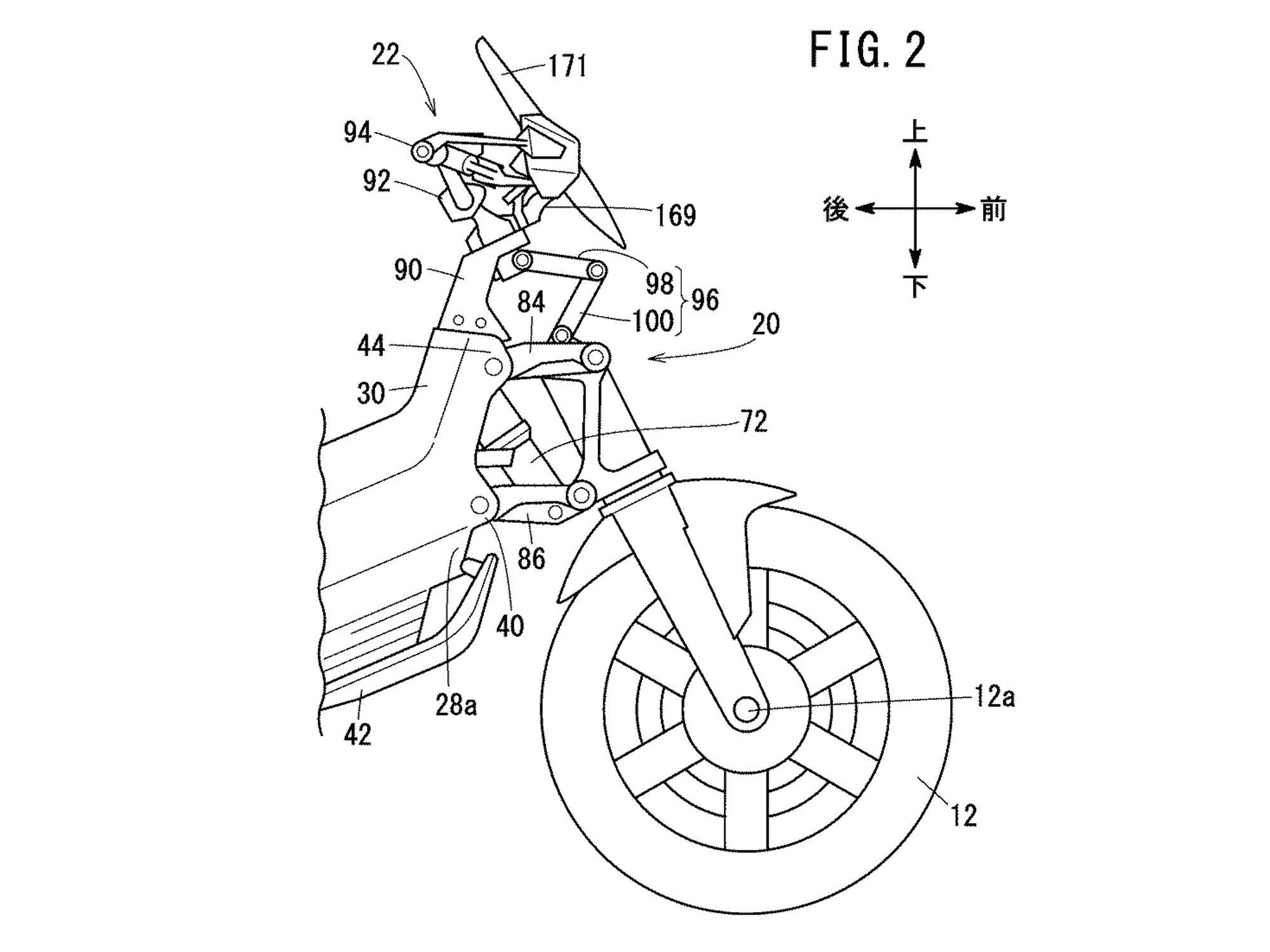

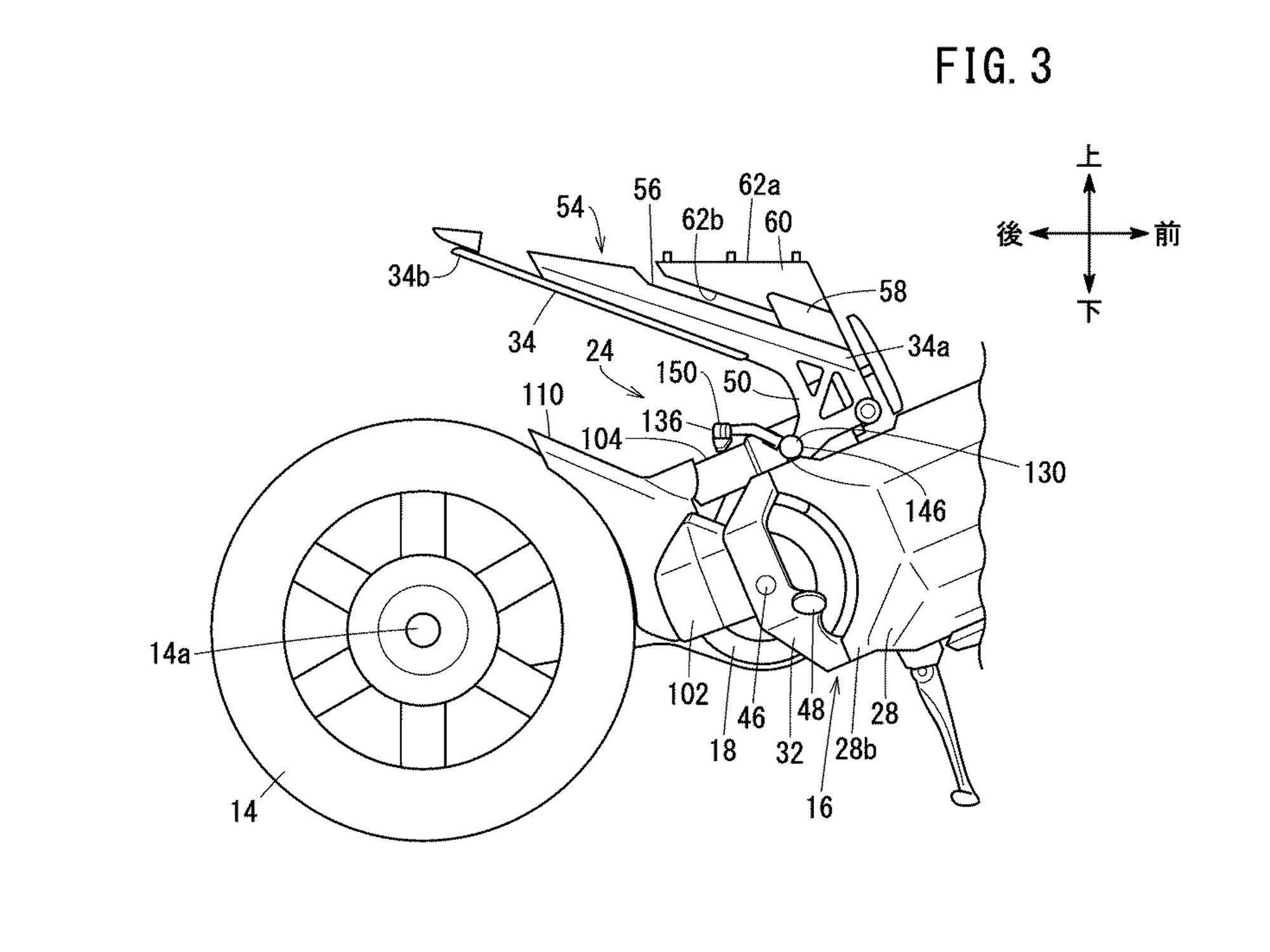

Will we see an electric Honda fun bike in 2022? If so, it could look something like this concept seen in recent patents. (Japanese Patent Office/)Electric motorcycles might be the future but at the moment they still account for a tiny proportion of sales and the world’s major bike firms are stumbling when it comes to working out how to introduce them into their ranges. Some are going down the scooter route, trying to appeal to young city dwellers attracted to the eco credentials of an electric bike, but otherwise offering little incentive to persuade existing motorcyclists away from their combustion engines. Others, like Harley-Davidson, are aiming their electrics at the other end of the market, with sky-high prices and appeal for early adopters but little in the way of genuine advantages over existing gas-powered machines. The new design from Honda, which has appeared in three patents filed in Japan, shows a third direction, and it’s one that might just hit the Goldilocks zone for electric motorcycles by attracting both young, eco-oriented new riders as well as existing motorcyclists intrigued by the idea of battery power.

Although it’s similar to a Grom, the new concept suggests a ground-up dedicated design featuring a Hossack-style fork arrangement. (Japanese Patent Office/)In terms of size and style, the bike appears to be positioned in the same space as the Grom; a small bike that’s intended to be fun above all else. The existing Grom, which has entered its third generation this year, has already managed to become a favorite among new riders and earned garage space among existing motorcyclists as a second, third, or fourth bike, sitting alongside something larger and more “serious.” While the Grom is gas-powered, if it was electric then the appeal would still be much the same. It doesn’t rely on performance, practicality, or long-range ability for its appeal, and since those elements are the usual drawbacks for battery-powered motorcycles it becomes the ideal candidate for conversion.

RELATED: Honda CB Electric Preview

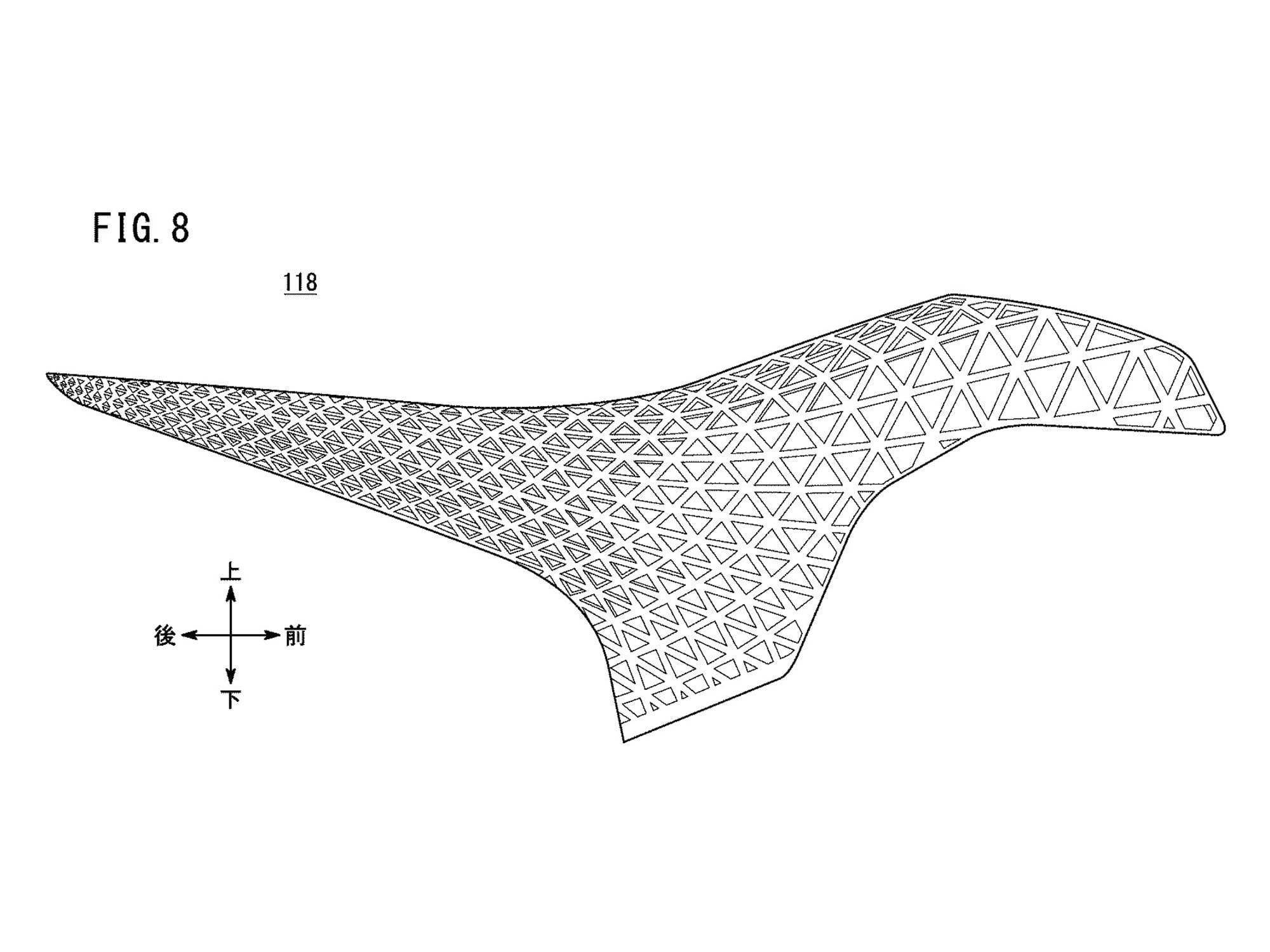

Monocoque-style chassis holds an electric motor at the rear, behind the battery. (Japanese Patent Office/)While Honda’s new patent shows a Grom-size bike, it’s not simply a battery-powered version of the existing model. Instead it’s a dedicated design, created from the ground up to be electric. The battery is held in a central monocoque-style chassis with the electric motor mounted behind it, while at the front we get a Gold Wing-style Hossack fork arrangement, with double wishbones and a monoshock bolted to the front of the battery case, holding girder-style forks. The bike looks perfectly suited to use the swappable battery system that Honda is already pioneering with its PCX Electric scooter in some Asian markets. Honda has now established a standard for such batteries as part of a consortium with Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki, as well as joining another consortium to do the same job with Piaggio and KTM, so it seems that’s the direction that the electric bike market is going to take.

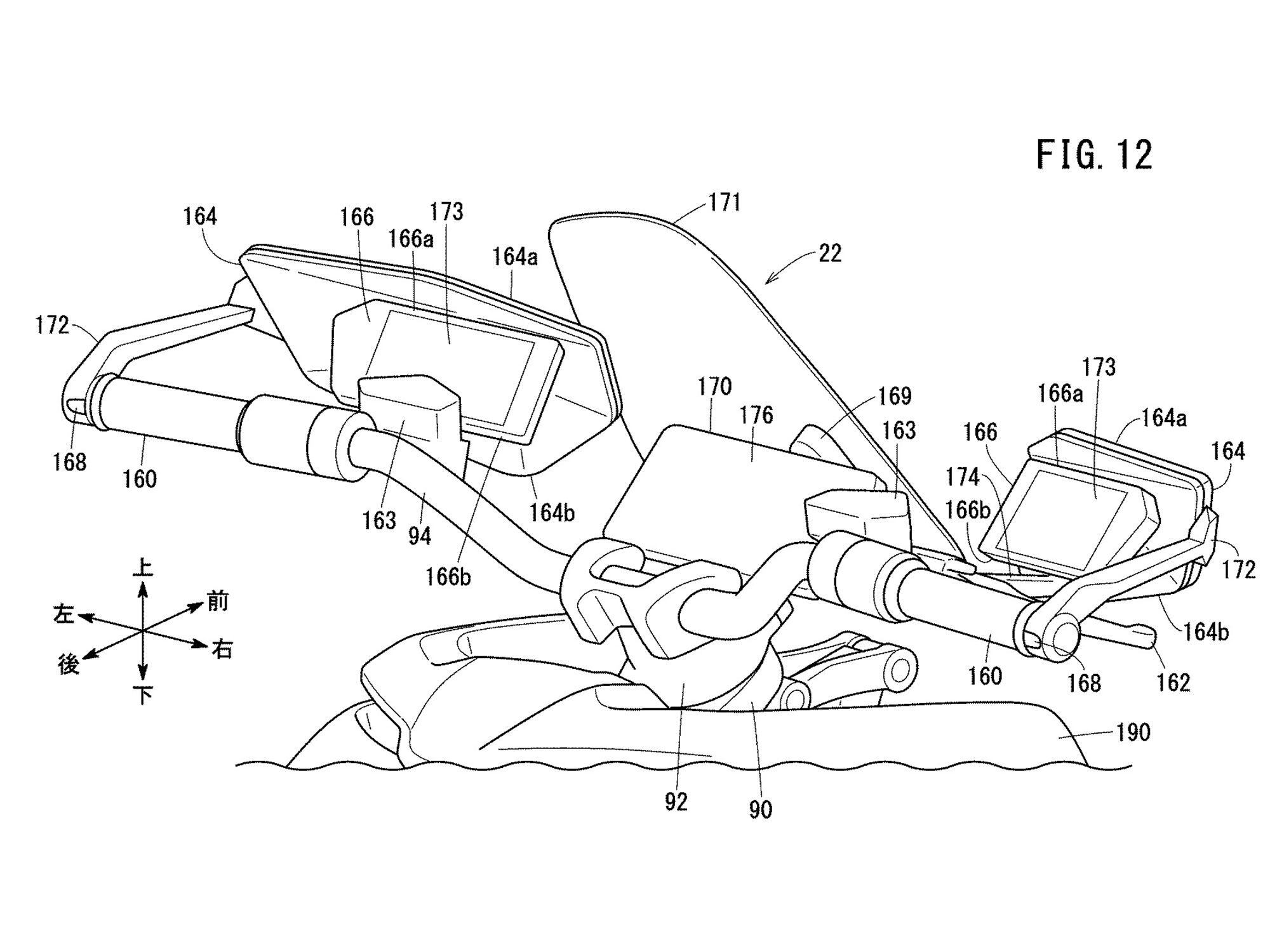

Patents show rear-facing cameras mounted in each bar end, though those likely won’t be seen on a production version. (Japanese Patent Office/)The bike in the patent appears to be a concept machine rather than something that’s heading directly to production. Had last year’s major international bike shows not been canceled, there’s a good chance it might have been officially unveiled at one of them. Concept-style details include a rider’s seat made of a flexible plastic mesh, rather like the back of a Herman Miller office chair, while the hand guards house individual TFT screens that replace mirrors. There are tiny rear-facing cameras in each bar end, transmitting pictures to these screens. It’s the sort of concept bike element that makes for a talking point on a show stand but offers no tangible advantage over a bit of mirrored glass in the real world.

Another concept-style detail is the flexible plastic rider saddle. ( Japanese Patent Office/)While there’s no guarantee that we’ll ever get to see this bike in the metal, and even if we do, it’s likely to be a concept rather than a showroom model, these patents are a clear indication that Honda is investigating the potential of electric power for bikes that are purely intended for fun instead of trying to compete with combustion engines on performance or practicality. It might just turn out to be a winning strategy in a world where electric motorcycles are still trying to carve a distinct niche in the market.

-

The KTM 1290 Super Duke RR. (KTM /)While sportbike fans still wish KTM honcho Stefan Pierer didn’t put the kibosh on a V-4-powered superbike based around the RC16 MotoGP weapon, there is some consolation in the news that the Mattighofen factory is giving its flagship 1290 Super Duke R the veritable Superleggera treatment—make that superleicht treatment—with the 1290 Super Duke RR. Limited to just 500 units worldwide, and not available in the US (more on that later), the RR is 20 pounds lighter than the standard Super Duke R.

Double Rs act as a signpost—they’re kind of fraught letters for lovers of two-wheeled high performance—and KTM engineers didn’t merely rummage through the PowerParts catalog with this one either (though they did that too). With a claimed 180 hp and 103 pound-feet of torque, and weighing in at a claimed 180 kilograms (396 pounds), the Super Duke achieves the coveted “1:1” power-to-weight ratio—at least if you adhere to the metric system. Engine performance figures aren’t improved over the standard model, even with its stock Akrapovič slip-on. An Akrapovič full system is also available.

The SD RR has LED lighting (low-profile turn signals!), cornering lights, and a slew of accessories from the PowerParts catalog. (KTM/)While it may not have an ultra-exotic carbon/magnesium/titanium main frame like some had hoped for when rumors of its existence surfaced, the RR does have a carbon fiber subframe/seat unit with a slick solo saddle. The whole bike is practically dripping in carbon; all the bodywork is made of the stuff, including the RC16-looking front mud guard and brake caliper cooling scoop.

Ultra-high-spec WP suspension components include Apex Pro 7548 closed-cartridge fork and an Apex Pro 7746 shock, which is a bespoke unit for the SD RR. An Apex Pro 7117 steering damper comes standard.

In order to reduce unsprung weight, KTM replaced the standard cast wheels with forged aluminum items that save around 3 pounds. The wheels are shod in Michelin’s stick Power Cup 2 radials.

Tidy tailsection, up-spec saddle material, carbon fiber everywhere. (KTM/)Interestingly, the SD RR uses a new throttle twistgrip with a 65-degree opening angle, compared to the 72-degree version of the standard model. KTM says it improves throttle response and ergonomics when giving it the beans (my phrasing, not KTM’s). For further low-hanging-fruit weight savings, KTM gave the RR a lithium-ion battery that’s around 5 pounds lighter than the lead-acid type—just don’t let it lose too much of its charge.

In the electronics department, there are new Track and Performance modes, which give riders what KTM calls “near-unlimited adjustability” for rear-wheel slip, throttle response, launch control, and Motor Slip Regulation (MSR). Basically, if you want to turn off or limit the electronic safety net and act like a complete goon, KTM will let you, which reveals so much about the MO of the mad scientists running the show back in Austria.

The 1290 Super Duke RR most certainly looks like a candidate for the most fun trackbike, even if it won’t be the fastest. (KTM/)European riders can begin placing online preorders for the KTM 1290 Super Duke RR on April 8, 2021. There’s no word on pricing, and we were unable to reach KTM representatives by the time we went to press.

Ready to Race. (KTM/)While we couldn’t reach anyone at KTM, we are curious if the SD RR will be available in the US at a later date. We already know the new 2021 KTM 1290 Super Adventure R isn’t heading to our shores until next year—which gives US dealerships a chance to sell a backstock of leftover 2020 models—so could it be possible that KTM is simply choosing to focus on the European market before boxing bikes up for far-flung dissemination? Given the supply chain disruption and all the other difficulties that manufacturers have faced in the wake of the global pandemic, it’s possible KTM just can’t deliver the bikes to the US in a timely fashion. So here’s hoping it eventually decides to sell the thing in the US.

-

Nick’s note: Alex Hatfield takes the reins this week to talk about consistency with weapons: rifles and motorcycles. Handled well, they are safe. Handled poorly, they are deadly. Alex is a Champions Certified Coach (3C) and heads into his rookie roadracing season with the USBA while working on his law degree.

Alex Hatfield competing at the 2015 International Sniper Competition. (Alex Hatfield/)The instructor glanced around the room, his rapid-fire lecture paused just long enough for our exhausted hands to finish taking notes on our equipment, history, and employment. “Now write this down,” he said. “Consistency equals accuracy.” It was day one at the United States Army Sniper School, and I had just written down a life-changing lesson, summarized in three words.

In the sniper community, accuracy is paramount. The primary mission of a sniper is to deliver long-range precision fire on key selected targets and targets of opportunity. The secondary mission of a sniper is the collection and reporting of battlefield information. The accuracy of our fire or reporting is a very real life-or-death issue. Miss a shot and your position is given away, an IED is planted, a buddy gets shot, or you get shot. Pass along bad information and an entire unit could be decimated (Anzio in World War II is a perfect, gut-wrenching example). The best way to achieve consistency is to reduce variables. Of all the variables we need to account for, the most important variable is the sniper.

If we can find a way to reduce ourselves as a variable, everything else becomes a math problem.

Backward planning helps: Start from the goal, work your way back. As sniper candidates, our goal was to be accurate. To be accurate, we must be consistent. To be consistent, we must reduce variables.

Shortly after arriving at the schoolhouse, we were given a reality check: There is no “secret sauce” to hitting targets beyond 300, 500, or even 1,000 meters. The difference between a trained sniper’s shot and a weekend shooter at a range is really just one thing: the degree of input application.

RELATED: Motorcycling Consistency: Part 1

Where a novice shooter might break the trigger by simply flexing his finger, the sniper smoothly builds pressure directly toward the stock. Both shooters have accomplished the same thing; the rifle has fired. Both shooters used the same muscle groups to achieve this, but the sniper is hitting the 1,000-meter target, while the novice is barely ringing steel at 100 meters. Why is there such a difference?

At 100 meters, not much matters when it comes to shooting a steel plate. There really is no wind to calculate for, no issues with determining target size, negligible Coriolis effect (deflection due to the Earth’s rotation), ballistic coefficients are just numbers on a box, and density altitude is largely irrelevant. In short, the 100-meter shooter becomes 90 percent of the variable influence on each round fired.

At 1,000 meters, a sniper must account for a laundry list of variables, and each of them has an influence on the shot. The Coriolis effect might influence 5 percent of each shot, the wind might oscillate between 40 and 80 percent during gusts, and so on for each variable. In order to consistently land rounds on the target, the sniper needs to reduce his own unintended influence on each round as much as possible to allow time and space to calculate for, solve, and adjust for each variable and achieve first-round hits.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Ask the sniper to shoot the 100-meter target. Round after round will impact in the same square inch of the steel, almost exclusively limited by the inherent mechanical accuracy of the rifle and ammunition. While the novice shooter may strike the plate repeatedly, the strikes are inconsistent. Why the difference? While both shooters are responsible for 90 percent of what the round does, the sniper’s actual influence on the round is minimal for two reasons: The sniper is consistent in his inputs, and his degree of application has much stricter tolerances.

“Cool,” you’re thinking, but what does this have to do with motorcycles?

Studying the art of going just a little faster. (Photo courtesy of Bluepants Media/)“Consistency equals accuracy” changed much more than just my approach to shooting; as it turns out, consistency is the key to being successful at many things in life, motorcycles among them. While our definitions of accuracy may vary, the concept remains unchanged. Develop consistency in the little things, and watch the bigger things improve. As Kyle Wyman once told me, “How you do one thing is how you do everything.”

Watching MotoAmerica, WSBK, and MotoGP riders click off lap after lap with tenths-of-a-second splits is easily one of the most beautiful examples of consistency in the world. The laser-like precision of riders as they recognize and react to markers or touch their knees (or elbows) down at the exact same spot on the tarmac every single lap is mesmerizing.

Much like a rifle, a motorcycle is designed by expert users and responds well to certain inputs. Like long shots, everything matters when you add speed. Like snipers, these national and world-class riders are consistent in their inputs and have extremely strict tolerances for those inputs.

I spoke with Nick Ienatsch, the founder and head instructor of the Yamaha Champions Riding School, about the similarities between sniping and riding. Nick said that there is one fundamental parallel between the two: “No two scenarios are the same.” Thinking back on both past rides and deployments, I had to agree. “The only hope for consistent success,” he continued, “is what the shooter/rider does. Our consistency removes one variable. If that consistency is best practices, then we succeed. If that consistency is second-best, then we are mediocre and intermittent.”

Mediocrity as a rider or shooter is evidenced by two things: loose tolerance of inputs and inconsistency. This may appear as sloppy trigger pulls, clunky braking, missed shifts, fumbled groupings, or failure to control fork rebound.

Looking on jealously as Nick Ienatsch enjoys a warm jacket on a cold day. “Man, those old guys are smart…” (Yamaha Champions Riding School/)In both dangerous professions and dangerous sports, mediocrity kills. The same MotoGP, MotoAmerica, or WSBK riders who are pursuing consistency are statistically much safer than the mediocre rider out exploring twisty roads on a Saturday.

One of the two leading causes for death on a motorcycle is simply running wide in a corner; a rider-error mistake. While the stakes of being a mediocre racer are typically sliding across some tarmac in a leather suit and a very short career, the stakes of being a mediocre rider on the street are all too often an ambulance or a casket. Where does this acceptance of mediocrity for street riding come from?

The motorcycle education industry has largely failed to instruct students in best practices when it comes to the fundamentals and processes of riding. Riders are taught unsafe and outdated techniques in the worst environment possible: new rider courses. I have seen (and taught, mea culpa) curricula that forbade covering the brake, mandated straight-line braking, and studiously avoided demonstrating what smooth control input looks or feels like. These bad habits are drilled relentlessly by well-intentioned instructors, but the fruits of their labor are generally riders who will never attend another class. Good habits like trail-braking, covering the brake, and weighting the inside peg are flatly rejected as “racing techniques” that are “unsuitable for street riding, especially to new riders.” Even the most well-intentioned and enthusiastic new riders can only achieve mediocrity if they are never taught the best way to ride a motorcycle.

Without intervening early in their education, these new riders are doomed to a Sisyphus-like existence: Rolling this stone of mediocre riding up a hill, wondering why riding is no fun until they get hurt or quit. If the student crashes and quits after attending their basic rider course, the instructor is likely to shrug it off as a lack of experience instead of lobbying for a change to the organization’s curriculum.

Hatfield coming to terms with his mediocrity after crashing his very first motorcycle, a week after graduating his basic rider’s course. (Alex Hatfield/)There is a common—and flawed—saying that pervades the riding community: “Practice makes perfect.”

Consistently applying poor technique will inevitably lead to poor results. Practice does not make perfect—practice makes permanent. The rider who is consistently snapping on the throttle, grabbing a handful of brakes, exclusively braking in a straight line, or throwing a bike into a corner is not reducing himself as a variable. These habits don’t really matter at parking-lot speed. Like shooting our 100-meter target, not much matters when we ride slowly; we have lots of traction and not much to worry about. However, as the pace picks up or available traction decreases, everything matters.

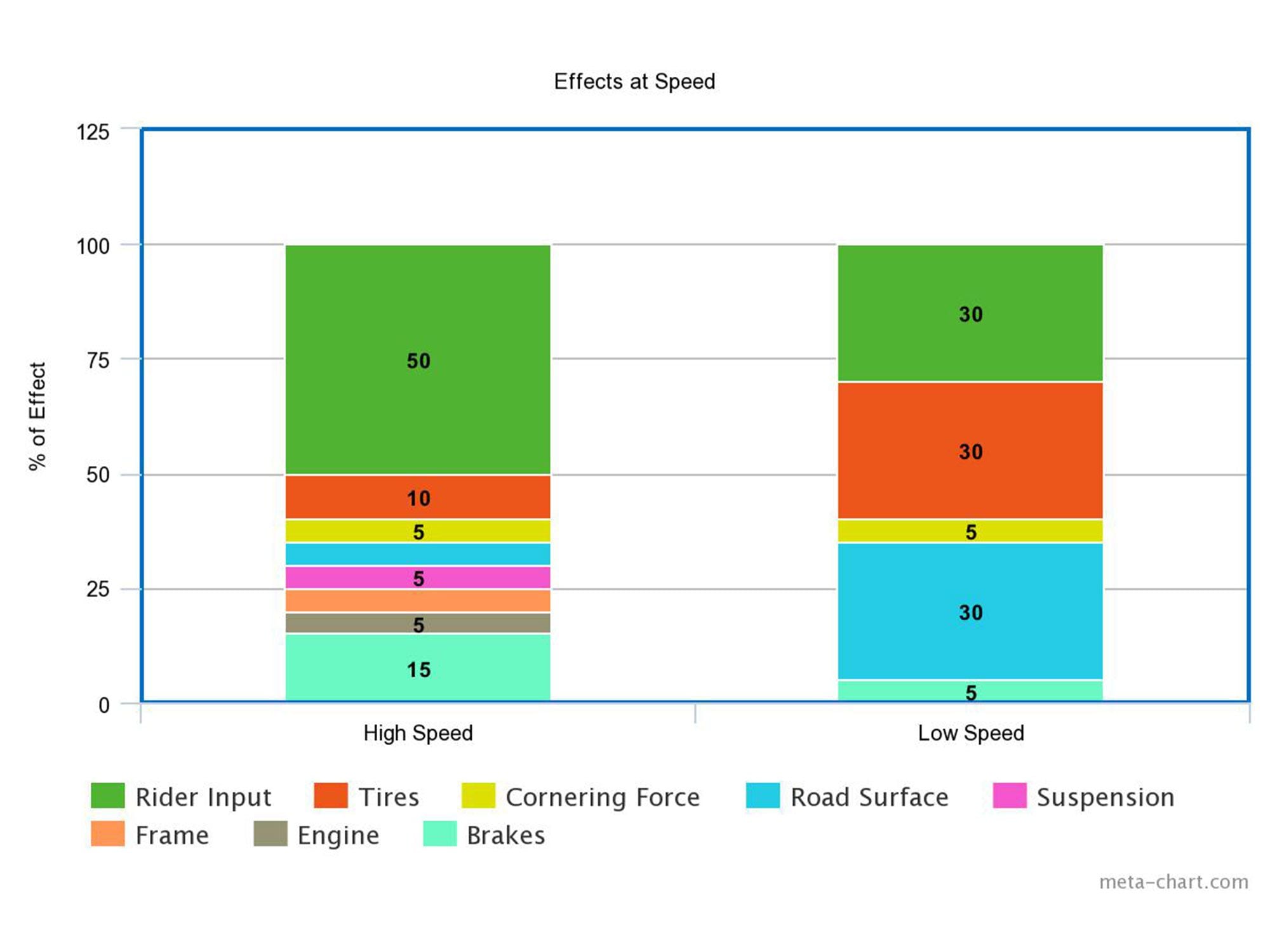

In Figure 1, we see that at high speeds, the number and effect of variables increases. Because there are more variables and because the effects of the rider’s inputs are magnified, an expert rider must work to reduce himself as a variable. (Alex Hatfield/)When we start going faster, our inputs become magnified.

A ham-fisted twist of the throttle results in a highside. Abruptly releasing the brake lever reduces our front tire’s contact patch and we lowside. Just like the sniper engaging the 1,000-meter target, we must work to reduce our unintended input on the motorcycle. By refining our degree of application and tightening our personal tolerances for inputs, we can overcome mediocrity. Working toward consistent inputs, we can effectively reduce ourselves as variables. As we achieve this consistency, our riding “accuracy” increases; our bike is exactly where we want it at all times, we stop smoothly and in control wherever we need or want to, and we enjoy every ride.

Perhaps more than anyone else on this side of combat, street riders are regularly exposed to wildly fluctuating conditions. If we continue to accept mediocrity in our own riding, we will continue to be a variable on every ride, on every street. The rider who practices good technique and becomes consistent in loading the tire before working the tire, who spends hours mastering the fine motor control needed to sneak on and release the first and last five points of throttle and brakes will have a safer, more enjoyable life on a motorcycle than the riders who accept the boulder of mediocrity. This safer rider understands how their inputs affect the motorcycle, is intolerant of their own sloppiness, and is consistent in their inputs. They can add as much or as little speed as desired or required and risk less in doing so.

By reducing themselves as a variable, these safer riders can enjoy riding for many years to come. However, not many riders are even aware of their impact on the motorcycle—much less how to correct it. The vast majority of riders will never step foot in a classroom dedicated to riding after they graduate their basic rider course. When I taught for a basic course program, the return rate of students after graduating their license-waiver course was less than 10 percent. In order to grow our sport and industry, we need to focus on eradicating the problem of bad habits, abrupt inputs, and mediocrity where it begins: basic rider education.

More next Tuesday!

-

Fabio Quartararo took the win at the Tissot Grand Prix of Doha. (MotoGP/)A week ago Sunday it appeared that Maverick Viñales had once more fought free of the bad luck that interrupted his brilliant beginning on Yamaha in 2017. His victory in Qatar 1 looked well judged, leading some to suppose that now, finally, he had decoded the mysterious “tire cypher,” transforming the appearance of randomness into a workable system. This weekend he started third, had one of his not-so-hot starts, and came around 12th on lap one. So much for the system (he fought his way forward to finish fifth).

This time it was Fabio Quartararo, also on Yamaha, who had the system. With discipline, he held station in eighth place for the entire first half of the race. Then he began an advance to the front, passing on average one rider per lap to lead on lap 19 (of 22). Those he passed were unable to reply, because their tires were done and his were not. If you look at Quartararo’s lap chart, it looks just like a stairway.

It recalled Marco Lucchinelli’s 500 championship in 1981, when he intentionally cruised behind the lead group, keeping his tires cool while they vigorously “post-cured” theirs into grease. Then, at half-distance, he advanced. He was able to ride around his rivals, now busy not crashing while he alone was still racing.

The stars of the start were Pramac Ducati’s Jorge Martin and KTM’s Miguel Oliveira, Martin shooting into the lead and Oliveira reaching fourth from 12th on the grid.

“It was a normal start, the kind we have been practicing in these times,” Oliveira said.

Martin accelerated all the way into the lead and he led the race for 18 laps, being overcome by Quartararo and Johann Zarco only at the end.

Rookie Jorge Martin led for 18 laps and finished on the podium in third. (MotoGP/)“I thought I didn’t have the pace enough to stay with the front guys, but then every lap was a bit closer to the end, and I say OK, another one, another one, and was keeping a good pace,” Martin said.

The new holeshot starting devices work fabulously, when all is well. Others either forget to engage them or somehow fail to get full effect:

Francesco Bagnaia said, “Unfortunately the holeshot device didn’t work well. I couldn’t insert it. It’s not easy to hook it up, especially when you have to stop at a precise point, like on the grid.”

He started and finished sixth.

Some are still calling Losail a “Ducati track” because Andrea Dovizioso won here in 2018 and ’19, and there is a longish straight where power can be decisive. Yet now Viñales and Quartararo, both on Yamaha, have won here this week and last.

Johann Zarco put his Ducati into second by saving his tires and energy. (MotoGP/)Bagnaia explained: “They (Yamaha) worked a lot in winter and on this track they are very competitive—at the level of Ducati. We have a lot of power but they have more traction so it was difficult for me to pass them on the straight. I would say it was a balanced situation.”

More traction enabled the Yams to launch faster off the last turn onto the straight, partially negating the Red River of Power.

If experience and understanding have value, Valentino Rossi should lead the way forward. But his weekend was a mysterious near-zero, ending in 16th place with no points.

“I lost too much time in the first laps. I wasn’t fast enough with new tires while there were a lot of riders that were,” Rossi said. “We still have to find more grip at the rear with the soft tire.”

Some will say Rossi’s career is over, but last weekend he qualified fourth—not a has-been achievement. Something about his riding clashes unpredictably with the present tire, and he hasn’t yet worked it out. The careers of many riders end when motorcycles or tires evolve in directions the rider is unable to follow.

It’s possible to imagine the rider’s experience as a slate, overwritten so many times that it is unintelligible. What does this new feeling from the tire mean? Try to look it up. Kenny Roberts once said, “I think of my mind as a big Velcro board, and hanging from it are all these packets, one for every situation, rider, or corner. My reflexes aren’t all that fast, so I try to get a lot of my thinking done ahead of time. That way, when something comes up, I just grab its packet and do it.”

Could there be such a thing as too much experience? Consider the remarkable performance of Jorge Martin, surging into the lead, maturely controlling the race for 18 laps, and only at the end being zapped to third by Quartararo and Zarco. Not bad for Martin’s second MotoGP start, and even better as refutation of the idea that younger riders are one-lap practice wonders who go backward in the race.

Where were the Suzukis, so lately lauded for their consistency and late-race grip? Álex Rins, fourth; Joan Mir, seventh.

And Jack Miller, so strong in practice and now Ducati team lead rider? He and Mir touched, entering the straight on lap 13.

“After that contact,” Miller said, “I lost three seconds but then I managed to do four really fast laps.”

He finished ninth after encountering arm-pump.

Do you see the contact as ground for an exciting argument? Two bikes, each designed for a different riding style, may have intersecting lines. That’s racing.

Take a step back and consider how different today’s MotoGP is from just a few years ago. At present the front half of the grid consists of superbly trained and highly experienced riders who have graduated from the intense competition of Moto2. They are not overnight Superbike sensations from the US, Australia, or the UK, smoking sideways into the lead. They have shown in the last two to three years that almost anyone in that group can win a GP. Yet not so long ago we were happy to have Kevin Schwantz to harry and challenge Wayne Rainey. We had five consecutive years in which no challenger at all arose to push Mick Doohan.

Today we think nothing of there being lead groups of six, eight, or even ten riders, pretty much nose-to-tail, looking like any one of them could reach the center box.

The field has been closer than ever so far in 2021 with just seconds covering the first 10 riders. (MotoGP/)The existence of these groups magnifies the importance of the start, because it’s not easy to advance in a group of riders having equal pace. Lost positions at the start translate into abused tires that just say no in the second half. As rider, equipment, and experience equality advances, it becomes ever more essential to do everything perfectly: Nail the start, understand and conserve your tire, yet keep the pace, ready for last-laps action. As Zarco noted after this Sunday’s second place, “…I was able to manage both my tires and my energy.”

A result is the variability we are seeing: No dominant champion emerges, head and shoulders above the rest. Instead, someone gets it right this week, and it’s someone else next week, and on and on. Very different from the heroic era of the two-stroke 500s, when at most three of the twenty-odd riders on the grid had workable odds to win.

Franco Morbidelli’s down weekend (he finished 12th, saying, “…My tires were finished too soon”) was kicked off by smoke from his Yamaha in FP1. The official info was that the problem was easily overcome and the affected engine still usable. What reversible condition could make that much smoke? Yamaha no longer gives out annual bike development info as it once did, but back in the day it told us it uses a crankcase evacuation pump to reduce part-throttle pumping loss. Normally such a pump is combined with low wall pressure oil scraper rings. The volume of smoke suggested a lot of oil or fuel being converted to vapor. The usual source is a holed piston (not easily reversible!), failed intake valve stem seals, or one or more injectors stuck on. Without further explanation this remains a mystery.

Franco Morbidelli’s Yamaha billowed smoke in FP1, but Yamaha said the problem was easily fixed and the engine was still usable. (MotoGP/)Aprilia has now become competitive, save in power. Aleix Espargaró made Q2 and qualified seventh, only to finish tenth.

“The bike works very well,” Espargaró said. “It also makes the tires work well, but this year on the straight is really difficult because every lap I lost a few positions from the middle of the race onward.

“In the last few laps I tried to pass Mir and Miller, I really tried in every way, but as soon as I got onto the straight they all passed me.”

As noted by two-stroke engineer Jörg Möller in 1978, “Horsepower? In four-strokes it is only money.”

There are few secrets in four-stroke race engine tech—it’s more a matter of how far you’ve had the time and money to push it. Aprilia can get there.

Interesting to see the latest fairing and wing evolution. Aprilia has come farthest in the race to have a single wing of maximum width, blended into the narrowed fairing nose that creates more wing room. This is quite different from the classic rounded subsonic fairing noses of three years ago, with a “designer stubble” of short winglets stuck on. In wing design, the longer the better. The turbulent region at wing tips, where the contrasting upper and lower surface pressures wrap around each other to trail an energy-robbing tip vortex, is a smaller part of the whole in longer wings. Long narrow wings create lift with less drag.

Aprilia’s fairing and winglet design has a single wing at the maximum width. (MotoGP/)Seeing this trend, some are likening the more extreme examples to the Fokker Triplane of 1918. The future of this trend is up to the rules interpretations of MotoGP’s tech man Danny Aldridge. Although decisions will sound legalistic, in fact this is such a vaguely defined area that it’s more a matter of “Yes, we endorse the trend of these changes,” or “No, we don’t.”

As I’ve noted before, one motivation to tolerate development is that most people can’t tell the difference between a production sportbike and a MotoGP bike. That can’t happen in Formula One, where no one can confuse an F1 car with a Porsche 911. Therefore, in the future I expect to see MotoGP bikes that no one can visually mistake for a production 600 with a lot of stickers on it.

Next comes Portimão and the heralded return of Marc Márquez to the grid. Mesdames et messieurs, place your bets.

-

Hello MOTORFORFUN,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

Hello Gonzalo,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

“I just like making the best stuff. Sometimes we do it just to do it, even if it might not be profitable.” (Jeff Allen/)“That’s my dad; he flew F-104s. I take a lot of inspiration from that photo,” says Christian Parker, owner of Rottweiler Performance, gazing at the black-and-white photograph of a man standing on the tarmac in his G-suit and helmet. “I see similarities between my father, a fighter pilot, and myself, a motorcycle rider. From the gear to the helmet to the mentality of what you are about to do, whether you are climbing into a cockpit or swinging a leg over a motorcycle. Those two very different things also seem quite similar.”

Parker’s fighter-pilot-like drive to be exceptional in every endeavor is echoed in every part of the 12,000-square-foot Rottweiler facility, from the bonkers 1290 Super Duke R that greets customers in the lobby to the billet-aluminum intake trumpets coming off the five-axis CNC machines in the back of the building.

“I just like making the best stuff. Sometimes we do it just to do it, even if it might not be profitable,” Parker says while describing the time and materials invested in a prototype titanium 890 Adventure R subframe. “They’re gonna be expensive. Who knows how many we will sell? Hopefully more than a few. Either way, people take notice.”

Parker founded Rottweiler Performance in 2011, and the shop has since become a go-to for those looking to get more power and performance out of their KTMs. Rottweiler specializes in the Austrian-made machines, as Parker has found KTM owners to be somewhat more fanatical about their chosen brand than others. This dovetails with his personal obsession of the well-designed parts that elevate KTM’s LC4-, LC8-, and LC8c-powered motorcycles.

Parker is continuously developing and creating new parts to improve KTM-based motorcycles. Current focus? The 790/890 Adventure R platform. (Jeff Allen/)Parker got his start in 1993 when he bought fabrication tools with the tax return money from his minimum-wage grocery store job. Trips to Baja, Mexico, with Phil Moore, his first fabrication boss, opened his eyes to the legendary off-road racing of SCORE and the machines competing in the Baja 1000 and 500. Soon after, he became a crew chief on Class 10 and Class 1 buggy teams, and eventually formed his own motorcycle team, leading them to multiple top 10 finishes. His work in Baja led to the opportunities to work for Rod Millen Motorsports as part of its Pikes Peak Unlimited racing effort, on a car powered by a 1,000 hp 2.1-liter four-cylinder engine built by Dan Gurney’s All American Racers and Toyota Racing Development. After that racing program ended as Toyota turned its focus toward the open-wheel-racing CART series, Parker headed back to running a team in the world of off-road racing.

His time in high-level racing had impressed upon him the importance of meticulous preparation to guard against failures. Parker started Rottweiler while simultaneously fabricating exhaust systems for bespoke Porsche customizer Singer Vehicle Design, and acknowledges that the money helped him build Rottweiler “the right way.” Rottweiler still makes the exhaust systems for Singer to this day.

But primarily, Rottweiler is the go-to for those looking to extract the most power from their KTMs, offering tuning, airflow, and hard-part options. And Parker’s reason for the focus on improving what the Austrian-based brand has achieved with its hard-edged machines?

“I bought a 2008 990 Super Duke to ride to Mexico to see my wife while we were trying to get her visa,” Parker says. “I just started to screw with it, like I do with everything, and made a bunch of power.”

Then people learned about the power gains Parker was making with his Super Duke. “The calls started coming in. I saw there was no one focusing on these bikes, so I went that direction. I pushed hard to create a whole world around them that made things understandable for the regular customer trying to make them work better.”

Chasing more power and performance in Rottweiler’s spick-and-span dyno room. (Jeff Allen/)Just past the row of parts-development bikes is a self-contained room with a Dynojet 250i dynamometer. It’s cleaner and more organized than a surgical suite. It’s here you’ll find Parker testing his parts and tuning while using a big-screen TV to monitor rpm, horsepower, torque, and air-to-fuel ratios. The display is such an important part of Rottweiler that Parker made sure customers can look through the shop and see into the dyno from the reception lobby.

Rottweiler’s latest undertaking is building a parts and accessories distribution business featuring brands that mesh well with the shop’s goal of building better motorcycles. As he walks through the brand new 6,000-square-foot warehouse addition, Parker explains that this is not something that can be achieved without a full commitment of resources, manpower, and space. His eyes have the same intense focus whether he’s talking about the warehouse or describing his new carbon fiber 890 Adventure airbox.

Whether sitting on a bike, working in the dyno room, designing parts in his office, building Rottweiler’s distribution warehouse, or preparing motorcycles, Parker is dead set on one thing: making motorcycles work better. That intensity is working for Rottweiler.

-

Hello Pentaeu,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

Hello Dan HTREP,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

Hello Gavlaw1,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

-

Hello Mr Goodwill,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

Hello Catton101,

Welcome to The Motorbike Forum. Please feel free to browse around and get to know the others. If you have any questions please don't hesitate to ask.

Why not tell us a bit about yourself too.

-

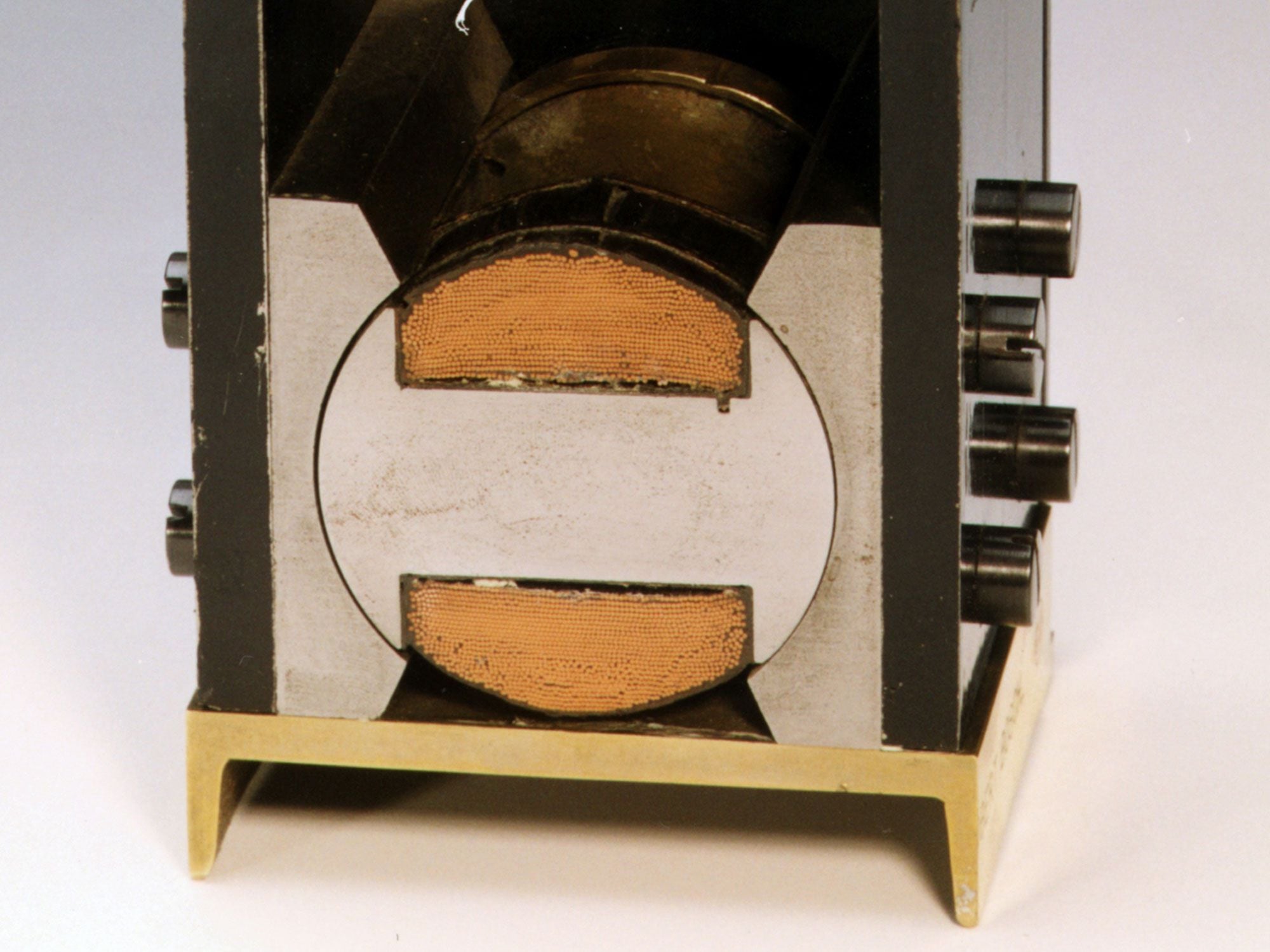

Fast Freddie Spencer learned that adding a touch of throttle at the right time would allow a front tire that had been pushed past its limits to regain traction.One of my greatest pleasures is when I finally understand some conundrum that has festered in the cold case file for too long. Back in the 1980s, standing at the fence on the approach to Daytona’s turn 2 (aka the “International Horseshoe,” a 180-degree right-hander), I tried to make sense out of what I was seeing. I’ve written about this before, but what it came down to was that decent 250 riders began acceleration over there, and World Champion Anton Mang began acceleration sooner than that, but I could hear Freddie Spencer’s engine start to pull just as he neared full lean on corner entry.

Brave, braver, bravest? That’s the easy answer that tells us nothing, gives zero insight. That one rolled around in my head like the grain of sand that irritates the tender gray flesh of the oyster. Where was the sense in this?

What if the riding I’d seen in turn 2 wasn’t good, better, best? What if, instead of just being the earliest to throttle up, Freddie had no choice—entering the turn as fast as he did, he had to apply throttle or he’d lose the front end and fall down? And then I remembered a Dunlop graph in a 1950s book, a graph of tire grip versus applied load. It rose on a slope, softened, hooked over, and started back down. That graph implied that a rider could overload his/her front tire during corner entry, to the point that it reached “saturation”—being forced into the texture of the pavement until there was no more rubber-gripping contact area to be created by load. And if the tire at that point began to let go—”losing the front”—the conventional wisdom was that nothing could bring it back. You were done.

But what if, using just a bit of throttle, you transferred some of that excess load back off the front tire? Then its footprint rubber should rise back up the falling part of the curve, back to the “hilltop” of peak grip! And then I thought, “This has to be the origin of the old dirt-track saying, ‘When in doubt, gas it.’”

Years later Freddie and I had a conversation in which he said there’d been two dirt tracks in Kentucky that were more football-shaped than they were oval, “So you could kinda play with it while you were turning.” That’s how he’d discovered how to save the front with a whiff of throttle.

Once he’d found it worked on dirt, he naturally wondered if it would work on pavement. Soon he would try it. It did work, and how.

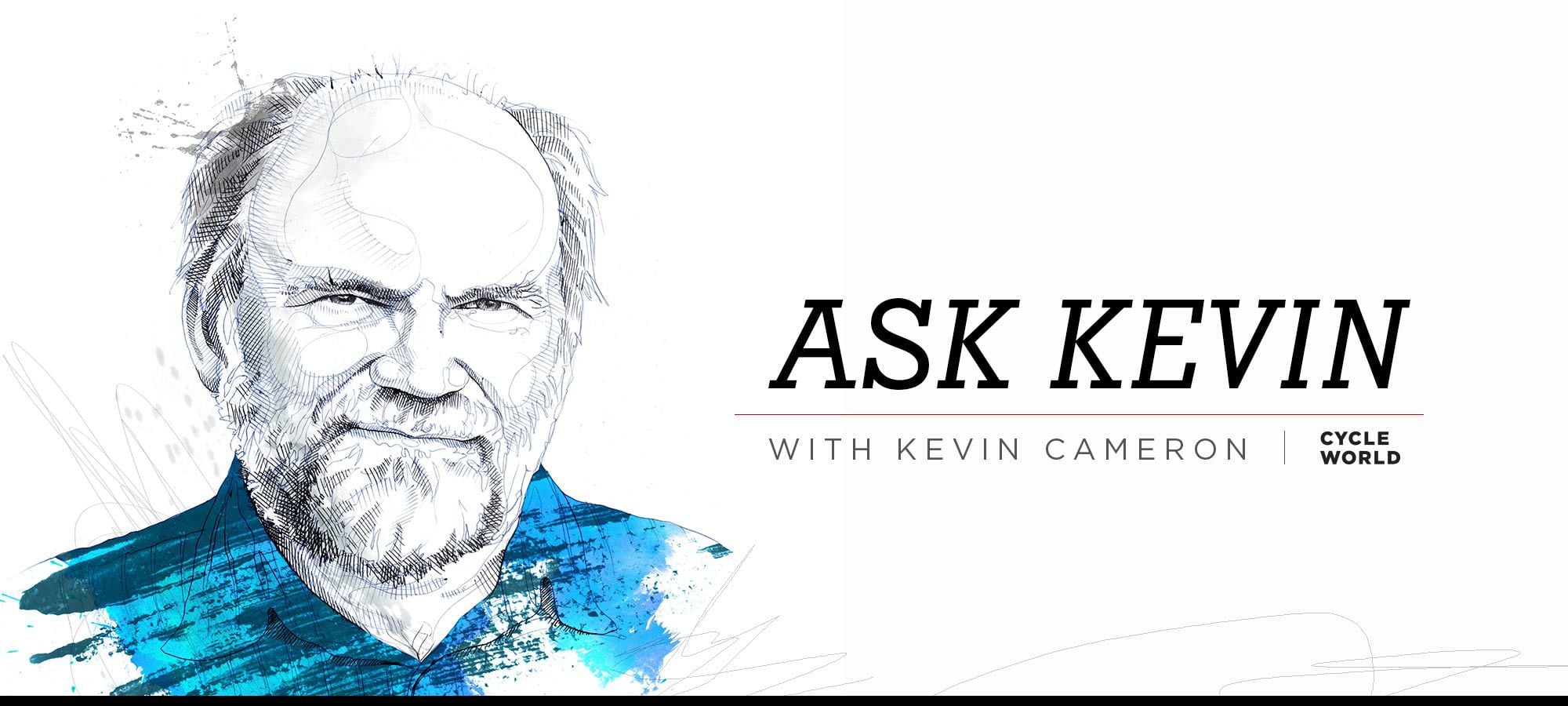

Recently I felt that same irritation as I read through the few references I have to the postwar two-stroke roadracers built by DKW in Germany. In 1951, nearly every builder of racing two-strokes was using the classic “blooey pipe”—an exhaust header pipe with an open megaphone on the end of it. Very loud, and not very satisfactory, because every builder knew that if you raised the exhaust port to enable the engine rev up past 7,500 rpm, the extra exhaust area that was still exposed as the rising piston closed the transfer ports would just let more fresh charge escape through the exhaust. That limited a 125 cylinder to 8 to 10 hp at about 7,500 rpm.

At that point DKW engineer Erich Wolf asked himself what would happen if he put some kind of reflecting wall or cone on the open end of the megaphone. With the right dimensions, that wall or cone should send a positive reflection of the exhaust pulse back to the cylinder, arriving there just in time to stop or reverse the loss of fresh charge through the open port.

Yet even with that tremendous invention applied to its three-cylinder 350cc, DKW was never, ever able to beat Guzzi’s one-cylinder 350 four-stroke. DKW factory rider August Hobl came close a couple of times, occasionally trading the lead with Guzzi’s Bill Lomas, but Guzzi won every 350 title from 1953 to ’57 inclusive. Hobl did, however, win German championships.

As with Freddie’s mysterious ability to get around corners, I found myself puzzling over how a low-revving 7,800-rpm four-stroke single could do the deed over DKW’s 9,500-rpm triple, which had the help of Wolf’s new baffled exhaust pipes.

Then I realized what must have happened. To take advantage of the new pipe, Wolf would have had to raise the triple’s exhaust ports, releasing the exhaust earlier in the stroke. This was necessary to blow cylinder pressure down quickly so that fresh charge, being pumped up through the transfer ports from the crankcase, could enter the cylinder, and allowing the engine to operate at higher revs. But releasing the exhaust earlier also meant that the escaping gas, having been less expanded, would be hotter. That hotter gas, rushing to the exhaust port across the piston crown, would have driven piston temperature up, increasing the danger of piston and ring scoring, or even seizure.

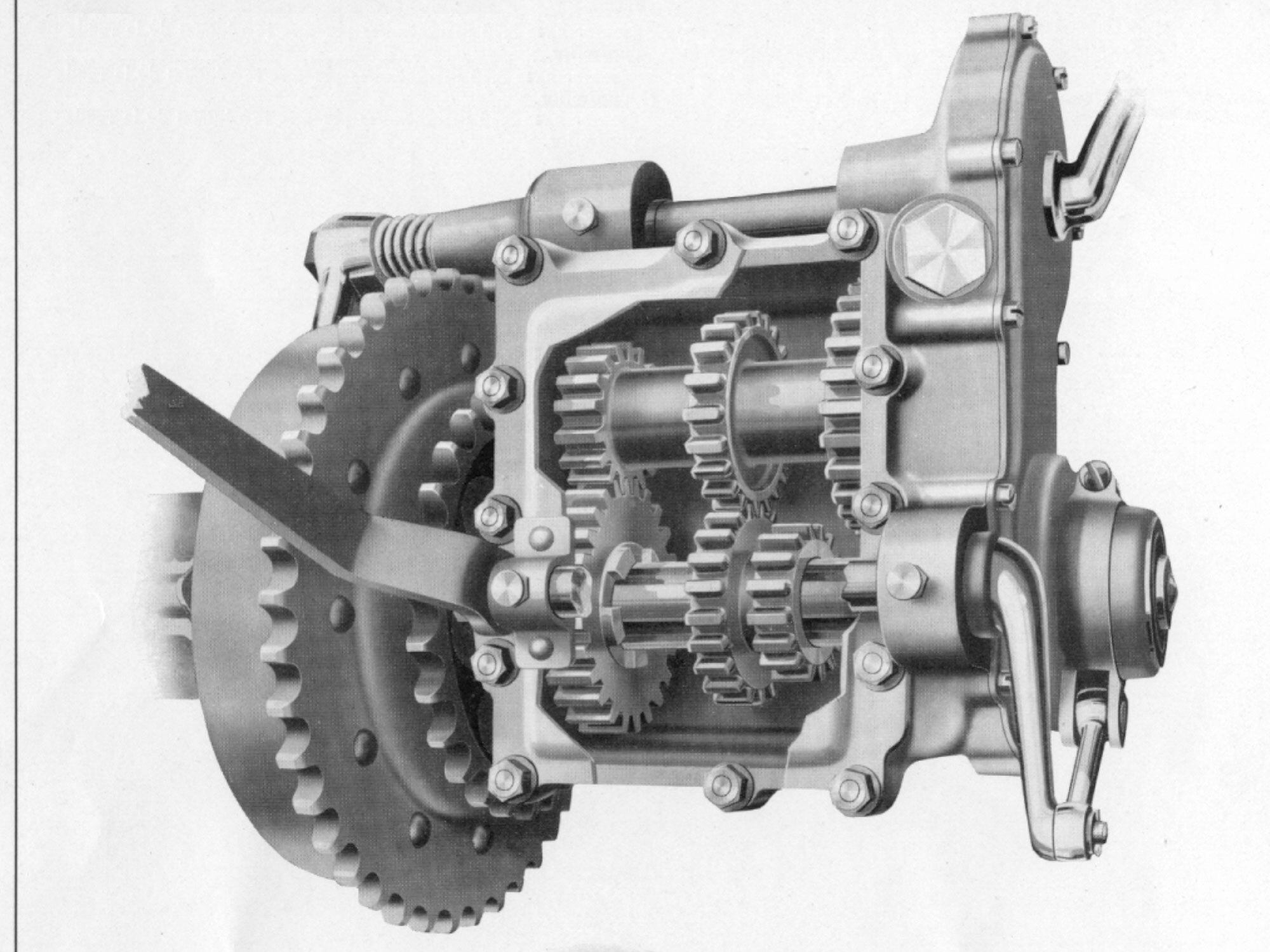

An early version of the DKW 350 with cable-operated drum brakes and big fat headers and pipes, starting at 32 hp and rising from there. Later the project was taken from Erich Wolf and tasked to Helmut Görg, who pushed the power to 45 hp at 10,500 rpm and adopted 215mm ATE coupled hydraulic drum brakes. The late smokestacks became skinny, with very long tailpipes. (Justin Dawes/)Therefore the rate of progress in matching earlier exhaust port timing to the new baffled pipe would have been slowed by the need to find piston alloys with greater hot strength and reduced thermal expansion. It would probably have required improvements to cylinder cooling as well. All that would take time, allowing the highly refined Guzzi four-stroke to continue to make hay in the class.

By the time I got my hands on two-stroke racing equipment in the mid-1960s, Yamaha’s piston and cylinder metallurgy had reached a decent level of reliability. With the Yamaha TD1-C of 1967, the last of the 250 four-strokes in US AMA racing, Harley’s Italian-made Aermacchi single, was driven from the class.

DKW had made its great contribution to two-stroke technology, its so-called “expansion chamber” or baffled exhaust, but it didn’t have time in which to fully develop it. The postwar German motorcycle boom erupted because in a destroyed Germany it was cheaper and quicker to get bikes back into production than cars. But when cars did hit the market, around 1955, Germans bought them instead of bikes. No more roadracing for DKW.

-

Riding the 2022 Suzuki Hayabusa in the canyons of Malibu, California, is a bit like taking a bazooka to a pistol range. You get a great sense of firepower, but really, not a taste of the full capabilities of the weapon. How far away is your target and how fast can you hit it? At least Malibu and the surrounding area isn’t all tight corners and bumps, so we had a few choice moments to explore the Hayabusa’s legendary firepower.

The 2022 Suzuki GSX1300RR Hayabusa is re-engineered and restyled with changes aimed at increasing “real world” performance and maintaining the Hayabusa legend. We did go fast this day, but here we’re going about 28 mph. It’s the job. (Kevin Wing/)Our 180-mile 2022 Hayabusa GSX1300RR first ride gave us a good taste of what this redone icon is all about, but it sure seemed a long way and long time from the original 1999 Hayabusa model launch in Spain. We had an amazing life-changing day dragging fairings and engine covers at Circuit de Catalunya followed by a day of “On-Road Touring” that ended up with us sixth-gear-pinned on a Spanish freeway about five minutes after ride departure. And we rode like that all day, doing things on a motorcycle that mortals had never before experienced, because no motorcycle had ever been as fast, powerful, and competent as the Hayabusa. Our original Cycle World testbike did a 9.86-second quarter-mile with a 146-mph terminal speed, and achieved a 194-mph top speed past the CW radar gun. On our in-house Dynojet dyno, it made 161 hp at the wheel and 100 pound-feet of torque.

Handling is remarkably good for such a large motorcycle. Steering-head angle is 23 degrees and works with a short 3.5-inch trail and longish 58.3-inch wheelbase for a fine combination of agility and stability. On tight roads, you’ll never forget you’re riding a claimed 582-pound-wet machine. On straightaways, you’ll think the bike is weightless. (Kevin Wing/)We will get full test numbers when we get our unit back at the office. Until then, I can say the new ‘Busa finds 145 mph in the blink of an eye and seems capable of lifting the front wheel at nearly any speed below that. And even though I burned less than a tank of gas on our ride, I have full confidence saying the bike’s superb balance and flexibility has been retained. It’s also still wicked fast—and remains big even if it is…lighter, perhaps? As a 6-foot-2 225-pounder, I feel right at home on the ‘Busa. Always have, from that first time I let the clutch out on pit lane at Catalunya and for the 12,000-something miles I put on our 1999 copper-colored long-termer. The Hayabusa was, in fact, my first long-term testbike when I was hired at the magazine.

Hayabusa enough for you? Sporty-bike styling of the last couple of decades has often mimicked stealth fighters, but the Hayabusa bucked pretty much every styling convention since its 1999 model year debut. (Kevin Wing/)As I approached the 2022 ‘Busa for my half-day ride from the hotel launching point, I thought the bike was more Hayabusa-looking than the press photos had suggested. I expected it might have gone a bit too lean-and-mean GSX-R, but in person it retains a strong family resemblance. The cockpit in particular is clearly descended from the first bike’s, with a similar damped-top-clamp treatment, large analog tach, and a speedo flanked by analog fuel and engine-temperature gauges. The bar damping is said to offer improved feel while also isolating bad vibes better. Our Glass Sparkle Black testbike with Candy Burnt Gold accents was a nice homage to the original bike.

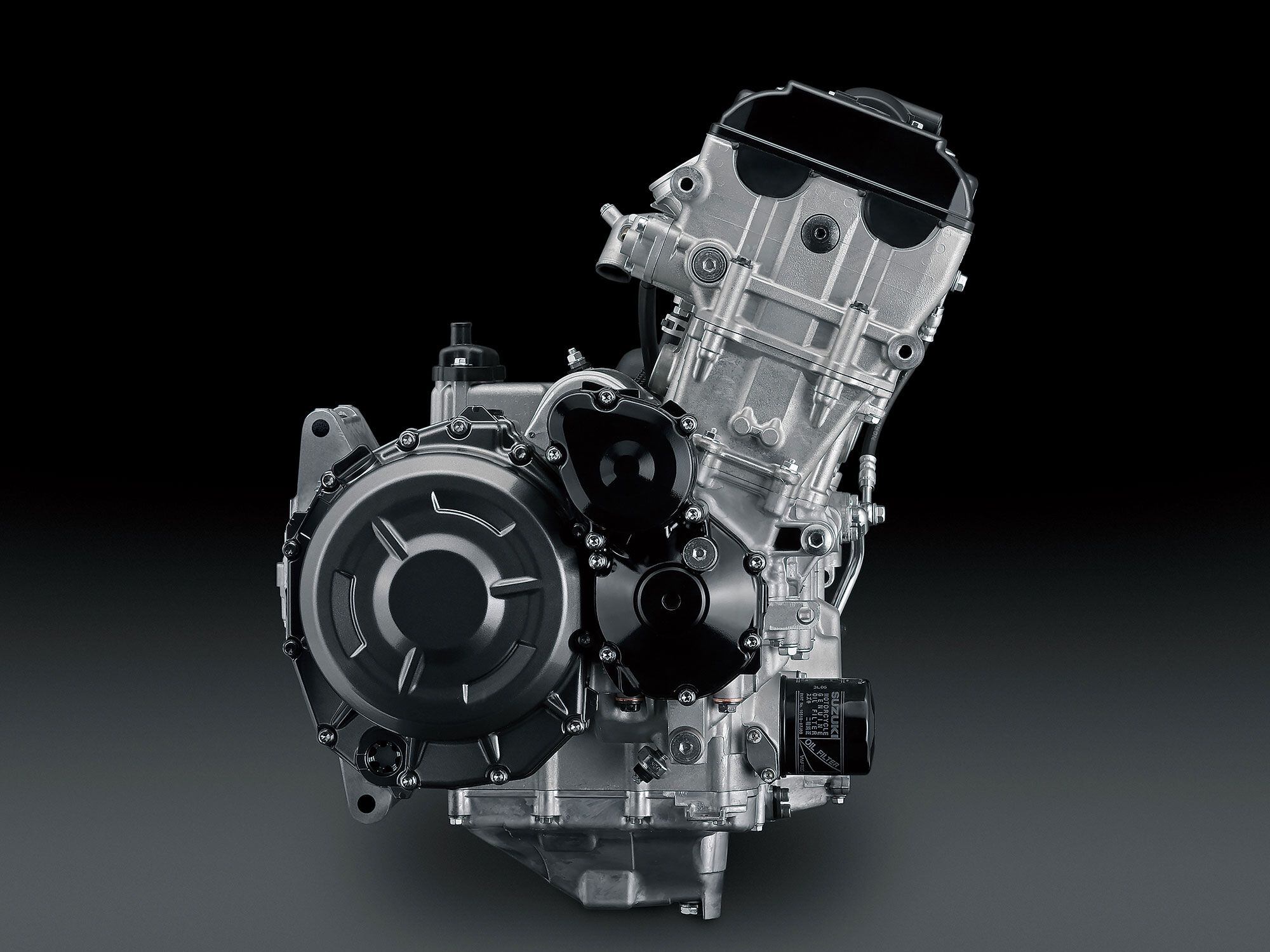

This is where all the magic happens. Meeting Euro 5 emissions while maintaining highest performance was the goal. Midrange is increased over Gen 2, though peak horsepower and torque output is lower. The <em>Cycle World</em> in-house dyno awaits to measure the true output of this remarkable 1,340cc inline-four. (Suzuki/)It’s no surprise that the bore and stroke of the 1,340cc engine are unchanged, and that the intake ports and exhaust ports have identical spacing as the previous Hayabusa. This way all that existing aftermarket go-fast equipment will easily fall into place on the redesigned, stronger bottom end. The frame has a similar design as the Gen 1 and Gen 2 ‘Busas, as well, and the overall effect is that everyone with ‘Busa tuning experience is going to know exactly what to do.

Release the relatively easy-pull clutch lever and you are greeted with great feel and absolute authority over the engine/transmission interface. You can feel its meaty strength as you slip away from a stop and feed in throttle. In fact, you can leave a stop in fourth gear with relatively little effort and idle along at 18 mph and about 1,400 rpm once the clutch is engaged. The engine could run all day in fourth, from this slow traffic speed all the way to about 140 mph in this one gear. Thankfully there are six gears to choose from, now with clutchless quickshifting both up and down.

Light steering, remarkable torque regardless of engine rpm, a bidirectional quickshifter, supple KYB suspension, and solid Brembo front brakes make riding a flowing backroad a true pleasure. Of all the big-bore hyperbikes, the ‘Busa has demonstrated the best overall balance and this remains true on the 2022 GSX1300RR. (Kevin Wing/)A few straight-line blasts in lower gears demonstrated that the Hayabusa’s eyeball-flattening performance is very much like it always has been. But it was grand to get onto the winding backroads of the Malibu mountains—bumps, rockfall, tar snakes, and all.

As we swung through the bends, all the torque needed for a brisk pace came while running 4,000–6,000 rpm. But when kicked up to 7,000–9,000, it started to get serious; you could really feel the rear tire start to work when exiting corners. Take it to the white-painted “happy zone” from 9,000 to the 11,000-rpm redline on the tach and… Holy warp drive.

“There are no lighting filaments on this motorcycle,” a Suzuki rep said in the tech briefing. Integrated turn signals and running lights are complemented by stacked headlights. (Kevin Wing/)We loved the raw gorilla nature of the original no-rider-aids ‘Busa of 20 years ago. But we have to admit the 2022 ‘Busa’s TFT display, found between tach and speedo, and its easy-to-use interface to manipulate ride modes, TC, lift control, ABS, and engine-braking control is quite welcome. So is the “active” mode, with its cool graphic representations of brake pressure, throttle opening, decel/accel force, and best for last, maximum degrees of achieved lean angle. I learned that 48 degrees of lean just keeps the footpegs from dragging. One item of note on that TFT display was that average fuel economy was set to Imperial gallons, for some reason; it read 31.4 miles per Imperial gallon, which translates to 26.2 mpg as we measure it in the USA. Suzuki claims fuel consumption is 18 percent higher than that of the previous model, so it’s burning more fuel. More definitive info to come with a testbike and lots of miles.

Basic frame design is similar to Gen 1 and Gen 2 twin-spar Hayabusa units. Gen 1 rake/trail was 24.2 degrees/3.8 inches, while Gen 2 got slightly more aggressive at 23.1 degrees/3.7 inches. (Suzuki/)The Hayabusa’s claimed wet weight is 582 pounds, 4 less than Gen 2′s, so it remains a heavy motorcycle, as is the class norm. It takes some convincing to get the Hayabusa to hustle through side-to-side transitions, and after about 20 minutes of riding I asked for more rebound damping to help keep the bike a bit better under control. It was helpful, and when we get a testbike to do a fully instrumented road test with horsepower and torque numbers, quarter-mile times, etc., we’ll dive more into chassis setup. Ride was plush, controlled, and ultracomfortable. On our ’99 testbike, I once left our old Newport Beach office at 4:30 on a Friday afternoon, burned north straight until midnight to Willows, California, for a two-day Jason Pridmore Star School at Thunderhill, then rode back after burning off the sides of the tires. I’d do that with this new one too.

Pity the brakes that have to haul down a heavy hauler like the Hayabusa. Lean-sensing ABS works with a full rider-aid Suzuki Intelligent Ride System to manage traction, wheel lift, engine-braking, launch control, and more. (Kevin Wing/)Brembo Stylema front brake calipers offer great feel and a lot of power. Suzuki says the new seven-spoke wheels (replacing three-spokers) give better feel for what the contact patches of the Bridgestone Battlax S22 tires are doing. I haven’t been on the last-gen ‘Busa for a few years, so I can’t say definitively if chassis feel is better on this bike, but I can say I felt confident in trail-braking hard (there is cornering ABS) and invoking traction control exiting corners, thanks to the delicate nature of the plentiful information transmitted through the bike.

A very Hayabusa cockpit with a color TFT screen to interface with rider aids and other menus. (Suzuki/)I had a ride leader and videographer on other Suzuki models along for our day, but Hayabusa-ing around as a group more or less demands other motorcycles with supernatural powers. After all, if Michael Jordan wants to play some pickup ball, he’s gonna have to be up against LeBron James for it to be any fun. Maybe a better analogy is the UFC and sparring with Roy “Big Country” Nelson; unless you’re a real animal, you just won’t hang. At any rate, a few corners and rapid blasts to redline meant I was riding alone most of the day.

Suzuki repeated much of the technical information about the new bike at the launch, but Technical Editor Kevin Cameron did an excellent overview, plus tech dives into the emissions/power/torque relationship and the improved durability/strength of key engine parts.

I think the key here, though, is the engine output discussion. Suzuki touts increased midrange horsepower and torque, and improved 0-60-mph and 1/8-mile times while explaining that peak power and peak torque output have been reduced, while also not revealing those numbers. We need to dyno- and acceleration-test the 2022 Hayabusa to know for sure where it stands, but the Hayabusa remains wicked fast. Rider aids and ride-by-wire throttle control may have softened its edge a bit compared to the original bike’s naked aggression, or maybe all the years between then and now have resulted in simply a more refined Hayabusa. Suzuki is touting it as “premium,” a luxury performance bike, and maybe that’s a strategy to cope with the reduced peak output and the $3,800 higher price tag of the $18,599 2022 model year Hayabusa.

Keeping engine revs in the 6,000–7,000-rpm range provided ample torque for spirited corner exits and to invoke traction control. (Kevin Wing/)But mere Earthly positioning conversations seem wasted on this bike, because really, all it’s ever needed to be is a Hayabusa. It is its own brand, its own specific thing, stronger than terms like “premium.” In this sense, reduced peak output does seem like a violation of the Hayabusa brand, and we have an interview scheduled with Suzuki engineers in which we hope to understand the challenges of meeting Euro 5 while maintaining high performance. Suzuki can say all it wants about how there is more usable power in the part of the rev range where you ride most, but the Hayabusa was never about usable power. The Hayabusa is about total dominance.

Crunching a few numbers shows the Hayabusa is geared to achieve about 213 mph or 340 kph at its 11,000-rpm redline. Top speed is, however, limited to 299 kph, as is the industry agreement. Tuners, get ready! (Kevin Wing/)Which makes this part of the conversation interesting: 3,100 rpm in sixth gear is 60 mph and basically idle-plus. Running 120 mph is 6,200, so set the cruise and effortlessly travel as far as the 5.3-gallon fuel tank will take you. This makes 180 mph a lazy 9,300, just when engine power starts to get good. Were it not for the voluntary 186-mph speed limiter that is the industry standard, and notably a result of the original bike’s 194-mph top speed, this would make 200 mph 10,300 rpm, 700 revs under the marked redline. Maximum theoretical speed with stock gearing would be just under 213 mph, which is coincidentally a tidy 340 kph.

On any list of top-ten most historically significant motorcycles has to be the Suzuki Hayabusa. (Kevin Wing/)Is it possible now that, because the Hayabusa has existed and expanded our perception of what’s possible for the past two decades, the impact of the new one isn’t the same as it was on that Spanish freeway clicking into sixth gear at 10,000 rpm on the 1999 model? Perhaps. But while the bike is more refined and somehow softer-edged in its new rider-aid-and-less-peak-power form, this is only our first taste of the bike. After a too-brief 180 miles in the saddle, I’d say Suzuki has nailed the ‘Busa feeling. It remains one of the most remarkable motorcycles ever produced. Definitively quicker and better? We have all the numbers from Gen 1 and Gen 2, and can’t wait to bring you the truth about Gen 3 on the street, race course, and dragstrip.

2021–2022 Suzuki Hayabusa Specs

MSRP: $18,599 Engine: DOHC, liquid-cooled inline-four Bore x Stroke: 81.0 x 65.0mm Compression Ratio: 12.5:1 Displacement: 1,340cc Transmission/Final Drive: 6-speed/chain Claimed Horsepower: NA Claimed Torque: NA Fuel System: EFI w/ 44mm throttle bodies Clutch: Wet, multiplate assist/slipper; hydraulic actuation Engine Management/Ignition: Ride-by-wire electronic Frame: Twin-spar aluminum Front Suspension: KYB 43mm inverted fork; fully adjustable Rear Suspension: KYB shock; fully adjustable Front Brake: Brembo Stylema 4-piston caliper, twin 320mm discs w/ ABS Rear Brake: Nissin single-piston caliper, 260mm disc w/ ABS Tires, Front/Rear: Bridgestone Battlax Hypersport S22; 120/70ZR-17M/C(58W) / 190/50ZR-17M/C (73W) Rake/Trail: 23.0°/3.5 in. Wheelbase: 58.3 in. Ground Clearance: 4.9 in. Seat Height: 31.5 in. Fuel Capacity: 5.3 gal. Claimed Wet Weight: 582 lb. Availability: June 2021 -

-

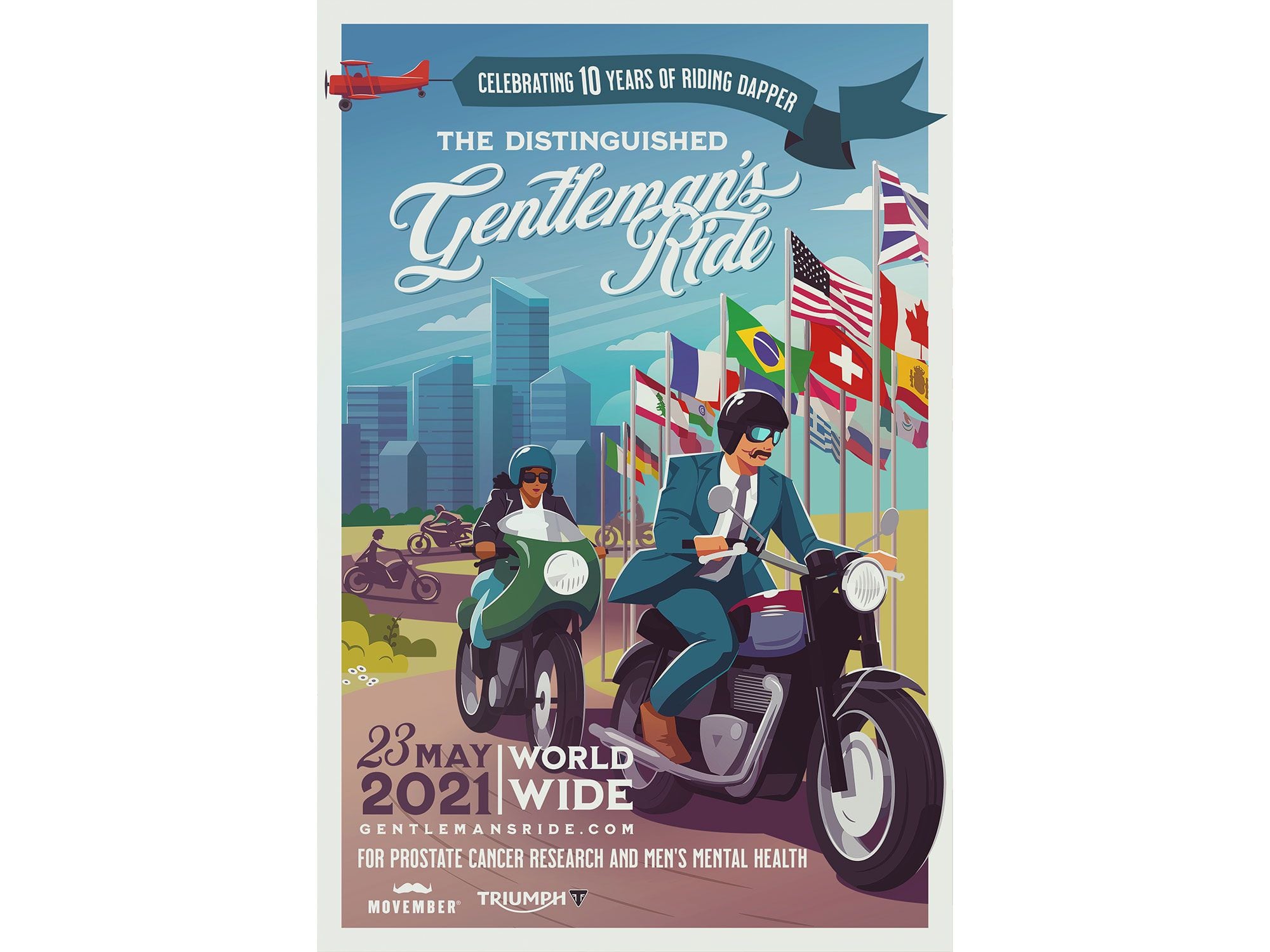

For 10 years, the DGR has been encouraging you to dress funny and ride classic bikes in the name of men’s health awareness. (Shane Benson/Triumph Motorcycles/)That dapperest of all moto events, the Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride, is back at it again for 2021, and this time there’s even more reason to celebrate, beyond the fact that it likely won’t be a completely solo ride event as it was last year. Or at least, we hope not.

As it has been for the last eight years, the ride is supported by Triumph Motorcycles which will help the DGR bring together classic and vintage-style motorcyclists on May 23, 2021. Also a big deal is the fact that this year’s event marks the 10th anniversary of the tweed-heavy hoedown, which has raised $27.45 million for men’s health causes since its first edition. Anyway, if buttoning up a waistcoat and waxing your mustache for a short spin on your bike sounds appealing, you’ll want to read on for the details.

Tweed jackets and handlebar mustaches: ATGATT for hipsters? (Shane Benson/Triumph Motorcycles/)First a quick sidebar. Apparently, somebody on the inside didn’t do the math last year; weirdly enough, the DGR had also claimed the 2020 ride represented the 10-year mark. But as the inaugural event was in 2012, clearly this year is the true 10th anniversary. Maybe they didn’t count last year’s ride because of the COVID-caused restrictions—as you may recall, 2020′s DGR was literally a singular one, with riders going at it solo instead of clustered in a massive pack of cycles, so it’ll likely be a bit of relief for some participants to be riding among a throng of classic rigs once again. Visually anyway, it’ll just look cooler.

RELATED: Triumph Partners With Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride

As a refresher, the Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride was created to bring together classic motorcycle enthusiasts to help raise funds and awareness of prostate cancer and men’s mental health. This year, the fundraising event is aiming for the milestone of raising more than $30 million on its 10th year anniversary, to continue funding research and programs with Movember, such as the Social Connections Challenge and the Veterans and First Responders Challenge.

The 2021 ride is once again being supported by Triumph Motorcycles. (Triumph Motorcycles/)To emphasize the DGR’s 10th running, this time around a one-off custom Triumph Thruxton RS will be built and revealed before the event, and it’ll go to the Gentlefolk Competition Winner for 2021. To get details on eligibility, register at gentlemansride.com and check out more event info there. As extra motivation, Triumph is donating four new motorcycles from its Modern Classic range to the three highest fundraisers worldwide.

As for this year’s ride structure, due to the ever-changing COVID landscape and restriction levels in various countries, the format of The 2021 Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride will vary depending on the location. For now, organizers say it will be a mix of COVID-safe, Route Only, or Ride Solo events. Check gentlemansride.com frequently to see how rides near you will be shaping up. All participants are encouraged to operate within COVID-safe best practices, and maintain appropriate social distancing measures. Follow the hashtags #DGR2021 and #ForTheRide to interact and engage with participants worldwide, which we’re guessing will also include the usual bike-riding celebrities seen in past events. If you’re looking for an excuse to break out the monocle or granddad’s vintage pocket watch on a ride, this might be your best bet.

One of the prizes you can win at this year’s event will be a one-off custom based on Triumph’s Thruxton RS model (stock model shown). (Triumph Motorcycles/)To learn more visit gentlemansride.com.

-

Kevin Cameron has been writing about motorcycles for nearly 50 years, first for Cycle magazine and, since 1992, for <em>Cycle World</em>. (Robert Martin/)I’ve written before about how motorcycles used to deal with vibration. The British parallel twins that would by 1972 numb riders’ hands, feet, and backsides, began life as little 500cc twins whose pistons were a small fraction of total vehicle weight. As a result, the vibratory “excursions” of bars, pegs, and seat were small.

“More power!” came the cry, and 500s became 650s, then 750s, and finally Norton’s 830cc. Those heavier pistons, plus the rise of revs beyond the 6,500 rpm of the original Triumph Speed Twin, added up to greater excursions.

My friends and I were busily building British twins in the mid-1960s and foolishly admired the gleam of aluminum fenders. Was it Dixie Cycle Supply that answered our call? Whatever the source, our engines effortlessly broke those light alloy fenders and their “universal” mounting brackets. It seemed that aluminum was a metal that remembered every insult. It was like the film badges worn by people working with radioactive substances, darkening with every hour of exposure.

Norton, under the stewardship of whichever greedy holding company was calling the shots at the time, did the obvious thing and developed the “Isolastic” system for separating the rider from much of the vigor of engine motion. Because both pistons of those British twins moved together, the engines orbited in a single plane; they did not rock from side to side. That being so, the engine and swingarm could be built as one unit, and the front end and rider/passenger accommodations could be built as another. The only relative motion permitted between the two units was in the vertical plane through the wheels; the engine’s orbital motion as it vibrated was restrained and damped by bonded rubber elements. It was a beginning.

When I first struggled with Yamaha’s furiously vibrating TD1-B production roadracer, I could see the chassis cracking in a pattern repeated in every TD I worked with. As the chassis was already quite heavy, I was sure they had originally prototyped something lighter and had increased tubing and engine mount thicknesses, probably more than once, until it took a season’s use to fail. And it was heavy.

We started to talk about “old metal,” for we knew that even as the lower left rear engine mount had broken, its mate on the right had undergone change that would soon break it in turn. Years later, in the pages of Bela Sandor’s Fundamentals of Cyclic Stress and Strain, I would learn that every stress cycle causes damage to metals. Individual atoms under strain are “uncomfortable,” and when a good-sized “jostle” comes along, they may shift slightly to reduce that strain. Rather like myself, trying to sleep in the passenger seat of a van somewhere in Nebraska. Over time, the sum of all those tiny relaxations, plus the occasional bond breakage, adds up to serious fatigue damage. That’s why airframes and racing valve springs have a predicted life. Continuing to operate a high-hours airframe beyond its three score and ten takes you into the territory in which cracks which lived below the surface for 10,000 hours are now emerging, ready to move more and more rapidly. Just think of the stress on the material at the very tip of a crack!

Yamaha had been making parallel twins for 18 years when the extra weight of the 1976 RD400′s 64mm pistons finally became too much. Many of us know that Yamaha engineer Masao Furusawa turned the company’s MotoGP program around in 2004, but less well known is the fact that it was this same vibration specialist who created the rubber mounting system for the RD400. A single-plane system like Isolastic could not work for the RD, because its engine also rocked like a double-bladed kayak paddle in vigorous use.